Find the Line Between Good Cold and Bad Cold for Citrus

During one stretch of freezing weather, Georgia citrus growers ran microjet irrigation for six days straight to help stave off cold damage.

Photo by Lindy Savelle

The level of interest and curiosity associated with North Florida and South Georgia citrus production is escalating. Some Floridians are reserving judgement, some are convinced that it is going to be a disaster, and others wish they could magically relocate their groves and infrastructure to the Northern counties. Why the variance of opinion? It seems what some view as a disadvantage, others view as an advantage. Let’s take a deeper dive into the attractions and the cautions.

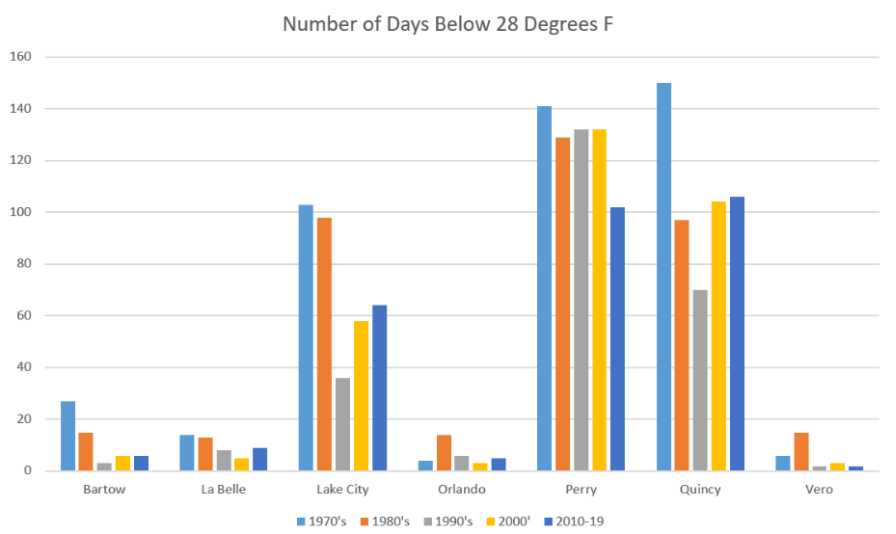

If we’ve heard it once, we’ve heard it a hundred times: The past few decades have produced less extreme cold temperatures, and the climate in Lake City is akin to what growers experienced in Central Florida in the 1970s. Rather than base this article on innuendo and gut hunches, I reached out to Daniel Brouillette, Climate Services Specialist at the Florida Climate Center, Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies at Florida State University. Mr. Brouillette pulled temperature data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (part of NOAA) from a range of sample locations in Central Florida, South Florida, the Indian River District, and North Florida. The focus was to examine the number of nights below 28°F. The assumption is that such nights may not cause catastrophic damage, but conventional wisdom would indicate that they certainly are an indication of elevated risk (with leaves, limbs and/or fruit). The results of the study are quite interesting.

What Does the Data Show?

Short of doing any rigorous statistical analysis, a casual review of the graph does reveal some interesting trends. The central, coastal, and southern locations (Orlando, Vero Beach, Bartow, and LaBelle) have experienced fewer days in the target cold temperature range than was true in the 1970s. The contrast is most significant since the year 2000.

Cold temperature range chart for Florida citrus

While Lake City and Perry show a clear downward trend in the number of days in the target temperature range, they still show significantly more cold nights than the Southern locations. The downward trend is not as clear with Quincy, except the fact that the 1970s were significantly colder than the other three observed decades. If you look at this data alone, it would be hard to conclude that the weather in Lake City today mirrors the weather in Orlando in the 1970s. But perhaps the target temperature range doesn’t tell the whole story. Is there good cold and bad cold?

Steady Cooling Vs. Rapid Shifts

The freezes of the 1980s wreaked havoc on Florida’s citrus industry. While there were record lows recorded in many areas in 1983 and 1989, it was the lack of acclimation or pre-conditioning that amplified the devastation. Relatively warm days were followed by extreme cold days.

Citrus trees will acclimatize when exposed to longer periods of gradually cooler temperatures. We see this with regularity in other states and production areas. Such trees are capable of handling much colder temperatures than trees that experience rapidly declining temperatures. Though rootstock and scion selection can help bolster the overall cold hardiness of a citrus planting, common varieties such as orange, tangerine, and even grapefruit seem to be more forgiving of colder temperatures when gradually exposed to more cool nights through a legitimate fall season. There are some beautiful grapefruit, navel orange, and Temple plantings in the border counties.

Dr. George Yelenosky, USDA Orlando, published an article in Plant Physiology in 1975 titled “Cold Hardening in Citrus Stems.” In this article, Yelenosky identified a two-week period with average day/night temperatures at 60°F to 40°F to establish cold hardening or acclimation.

Dr. José Chaparro, a Citrus Breeder with UF/IFAS, suggests that it may be informative to explore the ratio of the number of nights below 28°F, when proper acclimation occurred, with nights below 28°F when no such acclimation occurred. Although we were unable to use the available data to make this comparison, Brouillette summed it up nicely by stating: “I can say that, although freezes do occur less often in the Southern locations, they are more likely to come without any period of acclimation (i.e., high temperatures around 60°F and lows around 40°F). In the Northern locations, although freezes occur more often, they are more often preceded by a period of acclimation.” It would be a fascinating project for a graduate student to identify the geographic borderline (for each commercially significant variety), south of which the risk of freeze damage actually increases in an un-acclimated state.

Cooler Area Advantage?

Survivability is one thing but achieving superior fruit quality is another advantage of colder production areas that is rarely discussed. Northern counties are often able to achieve superior peel color that in many cases resembles that of a Mediterranean climate. Degreening is not generally needed, whereas degreening is now used throughout the season further south. Fruit grown in northern counties tend to achieve fruit size that is typical of Florida and subtropical areas. The combination of size and color is an attractive combination for growers.

Just One Night

Asian citrus psyllid (ACP) pressure is much lower in Northern counties. ACP and HLB are present, but not nearly at the level further south. Combine this with cheaper land prices and an ample supply of water for irrigation and freeze protection (some groves have separate poly lines for each function) and it almost makes a compelling case. However, the skeptical grower and nurseryman will tell you, “it only takes one night, and all is lost.” One night of sustained temperatures at 20°F or below could refocus the argument. Northern growers remain confident that they can handle the cold through variety selection, elevated microjet freeze protection, and natural pre-conditioning of the trees.

Author’s note: Special appreciation to Daniel Brouillette for his research and the National Centers for Environmental Information (part of NOAA) for this data.