Is A GMO Citrus Tree The Silver Bullet For HLB?

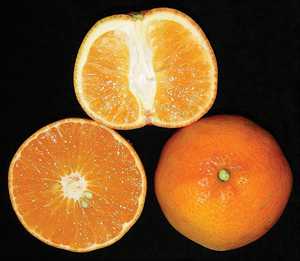

Transgenic trees (right) have performed well vs. non-transgenic trees in Southern Gardens Citrus field trials.

Photo courtesy of Southern Gardens

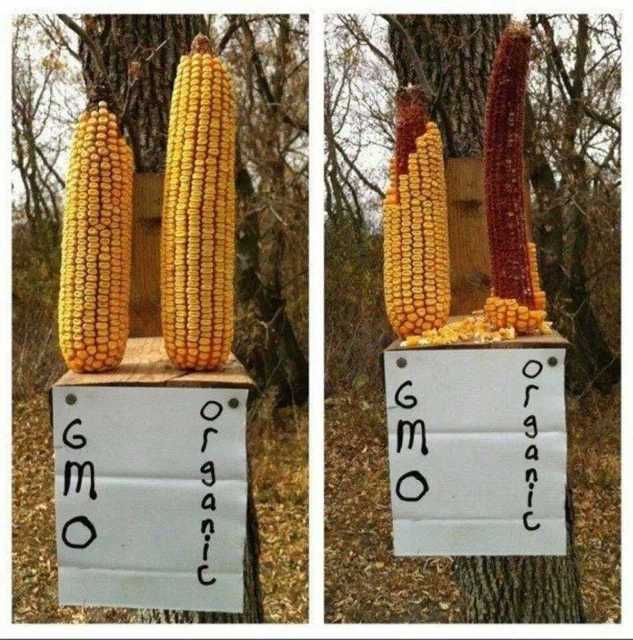

Some have called it the proverbial silver bullet — the genetically modified citrus tree. The prospect of a tree capable of resisting HLB or in some way warding off the psyllid could help solve a problem that has plagued the industry since the disease was confirmed in 2005. It is a bridge that science can cross at some point in the future.

But, with it comes a segment of society that believe genetic engineering is messing with the natural order with consequences to follow, despite a large body of science that states otherwise. Many of the prominent scientific organizations across the globe, as well as U.S. regulators, have deemed the technology safe.

Yet, a Pew Research Center study shows that while 88% of scientists believe genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are safe, only 37% of the general public agrees. Meanwhile, in 2007-2008, Florida produced 203.8 million boxes of citrus. Compare that to today’s production flirting with 100 million boxes. The disease marches forward despite the prevailing winds of public opinion.

Many believe the cultural practices growers have refined in recent years will carry the industry only so far in stemming the steady production losses brought on by HLB. Long-term solutions must find ways to defeat the HLB bacteria or its vector the Asian citrus psyllid. At the pinnacle of long-term solutions stands the HLB-resistant tree.

Early Innovator

Southern Gardens Citrus was one of two commercial growers to first identify HLB in its groves in October 2005. According to Ricke Kress, president of the company, more than 800,000 infected trees have been removed from its groves since the find. Like others, Southern Gardens is doing all of the cultural practices such as solid nutrition and aggressive psyllid control to stave off the disease as much as possible.

Photo courtesy of Texas A&M

“We set out to learn as much as we could as fast as we could,” Kress says. “We started working with our network of people from around the world who had dealt with this disease. We traveled to Brazil to see what we could learn there, because they had confirmed HLB 18 months before the U.S.”

Kress says the recurring message they heard was the ultimate solution would likely be related to some form of genetics. Soon afterward, Southern Gardens put together a variety of research projects aimed at the problem. By the middle of 2006, a genetically modified citrus tree was on the drawing board at its Clewiston headquarters.

“We knew we could not wait because a genetic solution will take time,” Kress says. “We pulled together our network of mostly university experts to evaluate risk and reward of each genetic trait.”

Why Spinach?

The gene Southern Gardens decided to move forward with was from spinach. Dr. Erik Mirkov, a professor of plant pathology and microbiology at Texas A&M University, isolated the gene he says encodes a protein that has broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacterial and fungal plant pathogens.

“The protein from spinach belongs to a large class of antimicrobial proteins known as defensins,” Mirkov says. “Defensins are ubiquitous in nature and are in plants, insects, and animals (including humans). They bind to the cell wall of the HLB bacterium and make holes in the cell wall, and the bacteria breaks apart and dies.”

Mirkov developed the trees in his lab, and with the cooperation of FDACS, brought the material to Southern Gardens for greenhouse testing and ultimately field testing.

“We put the first genetically modified trees in the ground in 2009 in controlled field trials,” Kress says. “All of these trees are planted and regulated as part of the federal government approval program. You don’t step out with any of this technology without concurrence of the federal and state agencies involved.”

Six generations of transgenic trees have been developed since 2009. With each generation, researchers refine the gene’s placement in the tree’s DNA to improve performance against HLB.

“We have a tree from our first generation that bore fruit this year,” Kress says. “Compared to control trees that are either stunted or dead, this tree is growing. It is showing a little infection, but it is growing. It is tolerant to HLB. It is a start.”

Erik Mirkov inspects trees at his lab.

Photo courtesy of Texas A&M

Southern Gardens has been working closely with state and federal regulators to shepherd the spinach defense technology along. All field trials are under strict regulations and any fruit that is produced from a transgenic tree will be under total control to ensure that none enters into the commercial stream unless and until all regulatory approvals are achieved.

“These agencies understand the magnitude of what we face with HLB,” he says. “They have been willing to work with us in every possible way. They have a job to do and there’s a reason we have the safest food supply in the world because of the laws and regulations in place. It is our job to understand those rules and advance this technology within them.”

Kress says Southern Gardens has invested into the “seven figures” to develop the GMO tree so far.

“We are still at the stage of proving this technology with the agencies,” he says “Once we get formal approval of the spinach defense technology, it will allow us to step out and do further testing. But, we are still talking years out. That’s why short- and mid-term solutions remain critically important.”

Science Progressing

There are more scientists studying how transgenic technology could benefit the citrus industry. Ed Stover, a horticulturist/geneticist with USDA at the U.S. Horticultural Research Lab in Ft. Pierce, is working with colleagues on more than a dozen research strategies involving genetic applications.

“So far, we have not found immunity to the HLB pathogen in citrus,” Stover says. “So we believe the insertion of traits to induce resistance through genetic engineering may offer us the best opportunity.

US Early Pride

“However, we have identified conventional citrus (US Early Pride and FF-5-51-2 in particular) with much greater tolerance to HLB than we see in sweet orange and grapefruit. Several of these varieties are going into replicated trials this summer to be compared against standard varieties in locations around Florida.”

Stover says a transgenic project he is excited about involves antimicrobial peptides. Like the Chimera in Greek mythology, the technology links two citrus defense genes together to fight HLB.

“We are working with Chimeral antimicrobial peptides, and with transgenics, we are moving these constructs into citrus with two citrus defense genes linked together,” he says. “Although these are citrus defense genes, they are produced at higher levels than standard citrus to make it more effective against gram-negative bacterial pathogens like Liberibacter (Las).”

Stover says other projects in their early stages would utilize RNAi technology to use DNA to produce double-stranded RNAi for psyllid and Las targets.

“It would suppress critical genes for the growth of the psyllid,” has says. “Another project using this approach disrupts the ability of the HLB bacterium to establish itself in the psyllid.”

Jude Grosser, a citrus breeder for UF/IFAS, is seeking tolerance/resistance to HLB using both conventional and transgenic tactics. He reports good progress on both fronts. In transgenic trials spearheaded by Manjul Dutt, oranges and grapefruit have remained PCR negative after four years in the field and some have remained PCR negative after two-and-a-half years in a psyllid hot house at Southern Gardens.

“We have made significant progress on developing more consumer-friendly GMO trees — ones where the inserted DNA comes from other edible plants, nothing viral, bacterial, etc.,” Grosser says.

Conventional Standouts

Grosser emphasizes that tolerance to HLB could still be found with conventional breeding techniques in the many trials currently evaluating potential candidates.

“We already have identified some very tolerant scions that sustain normal productivity and fruit quality when infected, if they are grown under an appropriate nutritional program,” Grosser says. “SugarBelle is the most tolerant commercial scion that we have. There are trees in the industry that have been infected for more than seven years, yet they look normal and are producing fruit with good quality on an annual basis under a good nutrition program.”

UF Seedless Snack

A new release, Seedless Snack, is showing the ability to grow through the disease with severe symptoms after infection, but strong recovery with good production and quality.

“Continued breeding will result in very competitive new cultivars with excellent tolerance of the disease,” Grosser says. “For example, this past year, we produced many new triploid hybrids from HLB-tolerant parents with outstanding fruit quality.”

Rootstocks will come in two waves. The first wave already is in trials from UF/IFAS and USDA and is showing reduced infection frequency (the tree becomes infected more slowly) and then showing reduced symptoms once infected.

“The field trials are now a contest to see which rootstocks in the pipeline can best grow through the disease under optimized nutrition that is needed to maximize the tolerance,” Grosser says. “The second wave will come from newer rootstocks that are now being directly selected for tolerance or resistance to HLB (with the ability to transfer this tolerance or resistance to grafted scions).

“I call our HLB rootstock screening process ‘The Gauntlet.’ We have gauntlet trees at the USDA Picos Farm that were grown from infected Valencia budwood and passed through a hot psyllid house before planting. After two years, several are growing off quite well, like a normal tree used to grow before HLB. These rootstocks are complex hybrids — some diploid and some tetraploid.”

The Public Perception Challenge

The Public Perception Challenge

The negative perception that comes with GMO crops can’t be discounted. On the front lines of the debate is the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) — the world’s largest trade organization for biotech companies. Florida Grower asked Karen Batra, BIO’s director of food and agriculture communications, about what the citrus industry should consider with a GMO tree.

What should citrus growers expect in terms of public reaction should a GMO tree for HLB be developed?

Batra: What we’ve learned is that consumers will have a lot of questions. It’s important that industry, government, and the scientific communities work together to demystify the science of biotechnology and tell the story about how science can help address problems such as citrus greening disease.

Research is showing us that by inserting genes from spinach plants into citrus trees, citrus trees can be more resistant to citrus greening. On one hand, people tend to me more receptive when the inserted genes come from other food crops such as spinach. On the other hand, this is likely to prompt questions like “Will orange juice taste like spinach?” and “Will it be green?” The broader question is whether or not people will drink orange juice that comes from genetically modified trees? There’s no reason why they shouldn’t. Billions of people eat GM food every day and have been doing it for decades without any health-related problems.

What should the citrus industry be prepared to do to promote public acceptance of GMO juice and fruit?

Batra: The industry should be prepared to answer questions and be proud to tell the story of how biotechnology can help save the citrus industry. Take a look at the story about the Rainbow Papaya and how biotechnology helped save Hawaii’s $17 million papaya industry. Be proactive and tell consumers about industry efforts to protect citrus trees and keep orange juice abundant and affordable, and be prepared to explain how juice from genetically modified trees is exactly like orange juice from non-GMO trees, only better because the trees are now able to fight a disease that is fatal for citrus trees.

Are you seeing any signs that public opinion on GMOs is beginning to turn?

Batra: We are actually seeing changes in public opinion on GMOs. Policymakers and media influencers are increasingly in agreement that safety and health is not an issue with GMO foods. For example:

- Mark Bittman, New York Times food columnist who has historically opposed GMO foods, wrote in May 2014: “GMOs are probably harmless; the technology itself is not even a little bit nervous-making.”

- At a Dec. 10, 2014 hearing of the House Energy and Commerce Committee on the FDA’s role in regulation of genetically modified foods, all six witnesses concluded GMO products are no less safe than their non-GMO counterparts, including Michael Landa, FDA director, Scott Faber from the Environmental Working Group and “Just Label It” campaign, and Rep. Kate Webb, assistant majority leader for the Vermont House of Representatives, who helped to pass that state’s mandatory labeling bill.

And the conversation in the digital space is trending in this same direction. Thousands of scientific studies have confirmed that crops and foods made with genetic engineering are as safe or safer than their non-GMO counterparts. International health authorities and national regulatory authorities agree.

Our GMO Answers website and related outreach programs have gone a long way toward answering common questions that consumers have about GMOs. We want to have an open and transparent dialogue with anyone who seeks information on these issues. The very fact that we are making transparency a priority is helping to turn public opinion.

The Future

While the idea of a transgenic citrus tree remains controversial in some corners, there is near consensus among the industry that research must explore every avenue of science and cultural practices where answers to the HLB question might be found.

And, all agree that an actual GMO citrus tree available to growers for planting in groves is still years out. That’s why short- and mid-term solutions remain so crucial to build a bridge to whatever scientists uncover for long-term solutions.

In the interim, the time is now for the industry to begin to prepare for the education process that will be required for public acceptance should a GMO tree become necessary to save Florida’s iconic crop.