Manage HLB From The Bottom Up

Photo by Frank Giles

This year will mark a decade since HLB was officially confirmed in Florida. Since that time, growers and researchers have been learning new ways to live with the disease and hopefully one day will defeat it entirely. Every season brings new lessons in what works and what doesn’t as the disease has become endemic across the state.

In January 2009, Florida Grower featured the pioneering work of Maury Boyd, who developed an enhanced foliar nutritional program to help trees maintain production in the presence of HLB. Today, enhanced nutrition is a standard practice across the state.

While foliar nutrition remains an important piece of the HLB-management puzzle, there has been growing recognition of the importance of root health in recent years. Dr. Jim Graham, a soil microbiologist with UF/IFAS-Citrus Research and Education Center (CREC), in collaboration with Dr. Evan Johnson, an assistant research scientist, have been working with growers to monitor root health and develop treatment regimes to help maintain it.

“We started seeing things on two fronts,” Graham says. “First, while trees performed better on enhanced nutrition programs, they still sometimes showed some off color in the foliage and experienced some leaf and fruit drop before harvest. On the other front, we started seeing evidence of other stresses, which lead us to recognize that bicarbonates in irrigation water and soil really cause trees to decline quickly. That all led to the same conclusion: There were serious problems with the root systems of these infected trees.”

Researchers have since documented that as much as a 30% to 50% reduction in root density can occur before HLB symptoms show up in the tree aboveground.

“We were very surprised by the order of magnitude of root loss,” Graham says. “We had never seen that kind of root loss with any other pathogen.”

While HLB infection starts in the foliage with psyllid feeding, the bacteria quickly transmits down to infect the fibrous roots of the tree and starts to reduce root function almost immediately.

“We now have studied this interaction between the pathogen and roots in great detail,” Graham says. “The infection occurs in the roots from the inside out and greatly impairs the ability of the phloem and conducting system to take up water and nutrients. It also predisposes the roots to be even more vulnerable to other pests and pathogens like phytopthtora, nematodes, and diaprepes root weevil.”

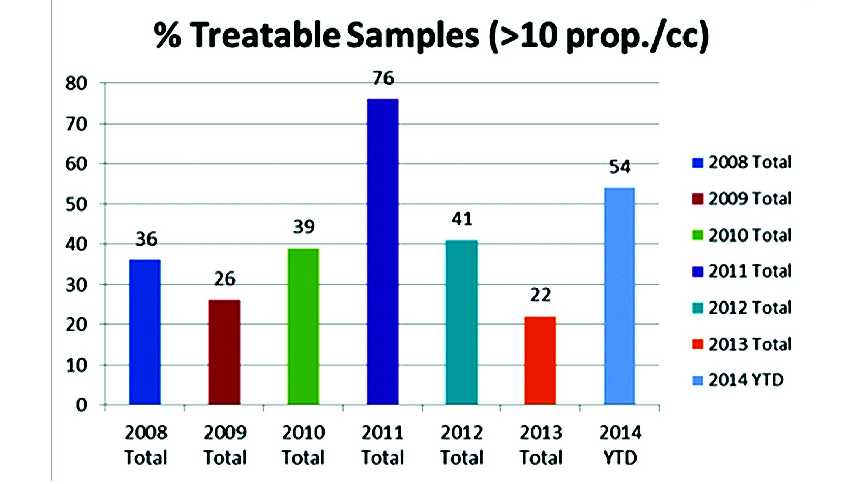

Evidence of this came with data being collected by Syngenta Crop Protection’s phytopthtora soil sampling program. The company’s statewide database showed phytopthtora levels rising very rapidly as HLB spread and levels dropped off almost as quickly.

“The HLB bacteria is causing unprecedented damage to the roots and the other pests are coming along for the ride and causing even more damage,” Graham says. “But, eventually as the roots die, these other pests and pathogens that depend on the roots for their support die too.”

Source: John Taylor, Syngenta

Syngenta’s data show a spike in soil samples that reached phytopthtora treatment thresholds in 2011 followed by a sharp fall-off the next year. According to Graham, that is evidence that roots were dying and unable to support phytopthtora. The fact that phytopthtora levels appear to be on the rise is a good sign, because it means there are roots available for the pathogen.

“Let’s call last season the worst case and a bottoming out of root and tree health,” he says. “We have seen some substantial recovery in trees this season starting last fall. Right now, Syngenta is measuring twice as many roots as last season in its program.

“Some of the growers I work with are reporting certain locations holding fruit like they have not seen in the past two to three seasons. But, there also are those who call saying they are seeing fruit drop like before. We are hearing some encouraging reports, but I don’t want to overstate it. This has a lot to do with a number of variables that come into play.”

Water And Soil Quality

A critical factor in the root health discussion has been the influence of water and soil quality on the ability of trees to cope with HLB.

“A lot of this has to do with bicarbonates in irrigation water and the soil and its impact on the rootstocks’ susceptibility to HLB and other pathogens like phytopthtora, nematodes, and diaprepes root weevils,” Graham says. “Some growers have begun to acidify their water and soil and are beginning to see trees performing better despite these issues with HLB and pests.

“So far, we are seeing some trees retain fruit better and foliage that is brighter and darker green in color. These appear to be sustained effects, not temporary.”

Root Health Checklist

Graham suggest growers measure bicarbonates in water and in the soil by taking well/surface water measurements and sampling soil pH in the root zone. The next step is to treat soil and water problems with acidification.

Photo by Arnold Schumann, UF/IFAS

“We are recommending getting the pH down to 6.5 in the water and soil,” he says. “We know that Swingle is the most susceptible rootstock to bicarbonates, so it is even better to drop the pH below 6.0.”

Once the bicarbonate issue is taken care of with acidification, growers should then turn their attention to other pests and pathogens that can negatively impact the roots. Graham cautions that acidification applications to the water and soil will take a full season to show benefits.

“You can monitor the effects of the acidification by looking for positive reactions in the trees and also by nutrient and leaf nutrient analysis,” he says. “If your leaf analysis shows improved calcium uptake, that is a good sign there are more functioning fibrous roots below to absorb nutrients.”

Graham says growers also are learning that applying fertilizer in smaller, more frequent doses through fertigation is helping root and tree health by spoon feeding nutrients to the root system. In addition, many growers are changing to their dry fertilizer applications to slow release formulations to avoid the big shots of nutrients that might not be efficiently absorbed by the weaker roots.

Graham also suggests growers consider removing unproductive branches of trees by hedging and topping with a floating bar. He calls the approach a “haircut”— not a heavy hedging.

“You cut off those branches that are unproductive,” Graham says. “You will stimulate foliar replacement with this kind of hedging to fill gaps in foliage, but in the process, you are not cutting off so much of the canopy.

Research at CREC has documented that if you cut off 30% of the canopy, you are going to lose 30% of the roots.

“The trees’ response to this is to replace the shoots first, then the roots, and then the fruit. You may lose a season of fruit production with that heavy of a cut. If you cut less drastically, that process is minimized. It is all about quickly restoring the right balance between the root and the shoots.”

Graham says official measurements have not been taken in groves where “haircuts” have been given, but observations have shown better fruit set responses in trees the following season, and growers have given positive feedback.

The Neonic Effect

Growers protecting young trees with soil-applied neonicotinoids are seeing some positive benefits outside of psyllid control.

“One of the benefits of using the neonics at the maximum label rate is the products induce systemic acquired resistance (SAR)reaction to canker,” Graham says. “The trees stay very clean of canker, and therefore have less stress.”

Graham adds the neonics provide a plant growth regulator effect that stimulates the growth of foliage and more leaf area.

“You get these large leaves partly because of the PGR benefits of neonics,” he says. “We are not talking about a miracle, but using neonics — along with all the other management tactics — appears to really promote early growth and production of fruit.”

Re-Planting Considerations

Graham says growers should replant on ground that offers the best potential for return on investment.

“If you have land with poorly drained, marginal soils with a high water table, do not replant those sites,” he says. “Move toward your best ground in terms of water quality, soil, and topography. Invest your money there whether it is resets or solid blocks.

Diaprepes root weevil

Photo by Robin Stuart

“In addition, if you have a property with endemic pests like diaprepes root weevil and burrowing nematode and you are not getting response to ongoing management tactics, you should consider not replanting in those locations either.”

Picking rootstocks that are less susceptible to bicarbonate stress also is important. Cleo has done well in tolerance. Newer rootstocks from UF-CREC and USDA were selected under high bicarbonate stress on East Coast soils, so they are naturally less susceptible. In addition, plant clean and quality nursery trees to get off to the best start possible.

Find The Right Mix

While preaching the root health message, Graham says growers shouldn’t abandon any of the other important management techniques developed over the past decade, including foliar nutrition and aggressive psyllid control.

“Managing root health is just part of the integration and balance of all these things we have been talking about,” he says. “But, all of these things have costs, so you need to be judicious and not go overboard on any of the practices. And, if there are products out there that have not yet been proven, test them first on one part of your grove against an untreated area of equal quality.”