The War on Citrus Psyllids Still Raging

An extreme close-up of HLB’s vaunted vector, the citrus psyllid.

Photo by Jeffrey W. Lotz

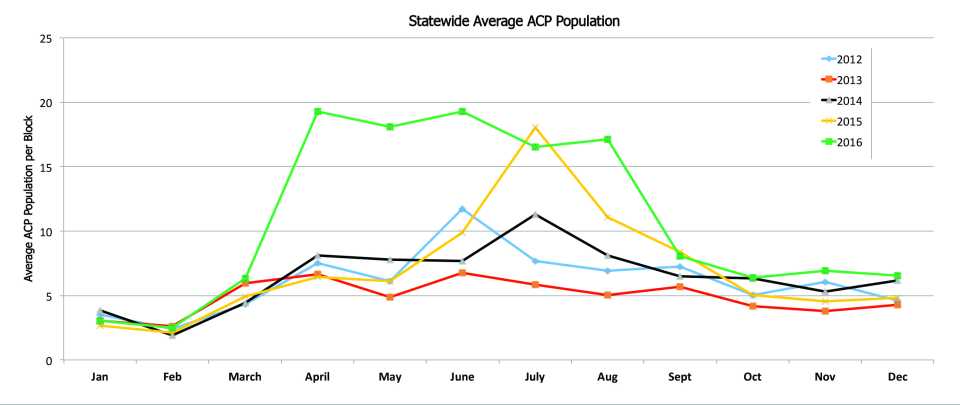

There has been plenty of talk about how high psyllid populations have been in Florida in the past year or so, and data collected by the state bears those stories out, showing historical highs for the pest. As the 2017 psyllid season kicks into full gear, growers hope populations return to more normal patterns.

“The psyllid counts throughout the summer we very high pretty much everywhere you looked,” says Brandon Page, Citrus Health Management Areas (CHMAs) Program Assistant for UF/IFAS. “If you follow population trends, the psyllids have followed historical data where they spike in the summer then start working their way down in the winter. But, for the better part of year, the pest was at record levels.”

Perfect Storm

There were multiple factors that could attribute to the historically high psyllid counts last season. Weather was a big factor with the record-breaking rainfall during the traditional winter dry season brought on by El Niño.

“In 2015, we saw pretty high populations of psyllids, and that was followed by a really wet winter in 2016,” says Dr. Lukasz Stelinski, an Associate Professor of entomology and nematology for UF/IFAS. “So, we had a high population going into the spring and a lot of growth on the trees because of the extremely wet winter.”

Stelinski says the flush and bloom in the spring was the perfect environment for the pest to thrive and procreate. With a particularly dry winter in 2017, he says the hope would be that psyllid populations would be lower since conditions were not as ripe for the pest to proliferate.

The wet weather in 2016 might also have impacted the residual control of pesticide applications on the psyllid. “If you went out with an application in the morning, then have a 2-inch rain in the afternoon, that would definitely be detrimental to efficacy.”

Another potential factor exacerbating psyllid populations is a symptom of HLB-infected groves. Groves tend to have some level of flush year-round, which gives the pest the ability to survive through what historically would have been slower periods.

Abandoned or poorly managed groves are a constant breeding ground for the pest as well. Those psyllids can move into groves where growers are trying to manage the menace.

“Psyllids can routinely move for at least a mile,” Stelinski says. “When they do these jumps, they can use alternative hosts for brief amounts of time to remain hydrated and perhaps consume some sugar resources so they can travel further. If you have a neighbor a couple of miles away that is not controlling the psyllid or is doing the bare minimum, you are in trouble, especially in the spring when the pest is moving about more.”

Other factors include when psyllids are at their worst during bloom, the use of some key pesticides is not allowed by label restrictions to protect foraging bees. Finally, economics might be driving some growers to make fewer applications.

“With the economic situation for many growers, you have people not spraying as much as they used to,” says Henry Yonce, Owner of consulting firm KAC Agricultural Research. “Some growers can’t afford to. It is a catch 22. You have less sprays overall and groves flushing year-round with the temperatures we have. We are not zeroing the psyllids out at any time.”

Citrus psyllid populations were at historically high levels in 2016.

Are We Seeing Resistance?

With numbers so high, there has been speculation and concern that resistance is developing. But, according to Stelinski, there is no “smoking gun” to indicate resistance.

“We have been managing psyllids intensely, so we have been tracking for resistance and have a data set going back nine years,” he says. “If anything, we have seen a reversal back to susceptibility in the last few years because growers have taken rotation seriously.”

While pockets of psyllid resistance have been documented, it is not a statewide affair. Stelinski stresses that monitoring for resistance and continued rotation of insecticides is extremely important to avoid the incidence of egregious resistance like that which is occurring in Mexico.

Control Options

While psyllid numbers have been high, many of the recommendations for control remain the same. Scouting and a low-tolerance for the pest remains important for growers hoping to keep groves viable as possible. Areawide sprays coordinated through CHMAs remain the most effective way to keep the pest at bay.

“You have to put psyllid control at the top of your production list,” Page says. “What is the one thing we have right now that can limit the spread of HLB? It is psyllid control. Another reason to spray is resets. We will never get them into production if as soon as they are put in the ground, they are torn up by psyllids.”

Dr. Phil Stansly, a Professor of entomology with UF/IFAS, says growers should scout and have a threshold for psyllids to trigger applications.

“Growers should be rotating chemistries during the growing season based on a threshold they are comfortable with,” he says. “If they don’t have one, then possibly one psyllid per 10 taps or five per 50 taps would work.”

If economics are forcing growers to reduce sprays, Stansly says there are certain applications growers should place a priority on. “Dormant sprays are the most necessary and effective against HLB,” he says. “I would urge growers to limit pyrethroid applications to the dormant periods and possibly border sprays.”

Stelinski adds the border effect is real and there is growing evidence that minding the borders is important. “Scout your borders and historic hot spots in groves,” he says. “If you are in a situation where you have to reduce sprays, consider spraying those borders and hot spots. You are not spraying the whole grove, but hitting the areas where the psyllids are most likely at.”

Stelinski adds the border effect is real and there is growing evidence that minding the borders is important. “Scout your borders and historic hot spots in groves,” he says. “If you are in a situation where you have to reduce sprays, consider spraying those borders and hot spots. You are not spraying the whole grove, but hitting the areas where the psyllids are most likely at.”

While there is not a set rule on what constitutes a border, Stelinski says any number of rows is better than no rows. “If you cover six parallel rows of trees from the edge, then you most likely are covering the borders,” he says. “But, that is not always tractable. Some is better than none.”

Photo by Wally Edwards

Targeting Abandoned Groves

The issue of abandoned groves has been a thorn in the side of growers striving to manage psyllids effectively. USDA estimates more than 100,000 acres of abandoned groves exist in the state.

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services has established the Abandoned Grove Initiative under the Citrus Health Response Program to encourage the destruction of these groves. The program works cooperatively with county tax assessors and property owners regarding abatement options and tax incentives to foster tree removal.

In addition, a second abandoned grove program is funded by the HLB Multi-Agency Coordination Group. Under both programs, growers will receive an Abandoned Grove Compliance Agreement upon completion of tree removal.

In-Bloom Options

When trees are in peak bloom, psyllids are spiking. Several pesticides are off the table due to EPA restrictions on foraging bees. Sivanto (flupryadifurone, Bayer), Movento (spirotetramat, Bayer), Portal (fenpyroximate, Nichino America), and Micromite (diflubenzuron, Arysta LifeScience) are labeled for use during this period. A newer botanical-based product Ecotrol Plus (rosemary oil, geraniol, peppermint oil, KeyPlex) also can be applied in this window and makes for a good rotational insecticide.

It is always recommended to avoid making applications when bees are actively foraging in groves. Read and follow label instructions.

The Bottom Line

As HLB has become endemic, there has been some discussion whether it make sense to even try to control the psyllid anymore. There is strong consensus among researchers that controlling the pest is a must. Research also indicates an aggressive control program is vital.

“Myself and other colleagues investigated psyllid populations under various management regimes from unmanaged groves to more intensively managed,” Stelinski says. “What we found was in groves that were moderately managed (three to four applications per year), the resulting psyllid populations were equivalent to doing nothing at all.

“Growers who are serious about continuing into the future will have to keep controlling the psyllid. Otherwise, the pest will lead to death by 1,000 cuts.”

“All of these various other inputs like fertilizers, bactericides, and other things have a much better chance for success if we are controlling the psyllids and reducing the inoculum,” Page says.

Going forward, there are multiple research projects aimed at taking the psyllid out. For example, the NuPsyllid Project aims to replace wild psyllid populations with a population that is unable to transmit HLB bacteria. In addition, other projects focusing on RNAi disruption of the psyllid are underway.