Saving California Citrus Means Thinking Outside The “Carton” [Opinion]

The California citrus industry is bracing for its toughest battle yet — the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP) and Huanglongbing (HLB), an incurable plant disease that is destroying the citrus industries in Florida, Brazil, Mexico, and now Texas.

The stakes are high. In Florida, more than 90% of commercial citrus trees are estimated to have HLB — where it’s sometimes called “citrus greening” — and the impacts to the industry and state are staggering.

The industry has endured a 70% (and growing) decline in production causing an economic impact in excess of $7.8 billion and more than 7,000 lost jobs. It’s a stark contrast to the vibrant California citrus industry that has persevered through drought, freeze, and onerous laws and regulations.

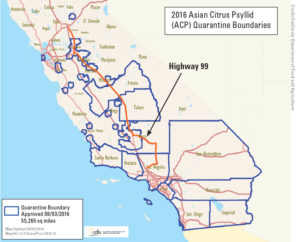

Asian citrus psyllid (ACP) is an enthusiastic hitchhiker. The pests are most frequently found along major traffic corridors such as Highway 99.

But we are not immune to HLB or the devastation it causes. The industry has faced this issue head on. When the psyllid was first discovered in California in 2009, growers supported legislation that mandated an assessment and created the Citrus Pest and Disease Prevention Program.

Since 2009, growers have invested more than $100 million into the program to stop the spread of ACP and prevent HLB from taking hold. Because of this investment, not in spite of it, HLB has now been detected in 30 residential citrus trees within a small geographical area in the Los Angeles Basin.

Public Relations Is Key

Outreach and education to homeowners has been a critical component to the multi-million-dollar program. There are more citrus trees in backyards than there are in commercial production, and it’s no coincidence that the highest level of ACP populations are in dense urban areas.

Extensive survey work, trapping, and research has lead us to the proverbial needle in the haystack. Education to consumers via billboard signs, public service announcements and various forms of advertising are measurably effective.

When the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) knocks on a homeowner’s door to tell them their tree is infected with HLB and must be removed immediately, the response is by and large positive.

When ACP is discovered near a commercial citrus grove and CDFA goes door to door in the surrounding neighborhood to treat residential trees, rarely does a homeowner refuse. This is evidence of a successful program.

The reality of additional HLB-positive trees is imminent, but when compared to the Florida narrative, California is ahead of the curve.

The insect and now the disease have spread at a rate far slower than elsewhere in the country and world where other citrus industries were not as proactive as our citrus industry has been. California citrus growers should be commended for their forward thinking, diligence, and optimism.

The Battle Is Far From Won

Recently California Citrus Mutual facilitated grower meetings in each of the state’s citrus production areas to evaluate the effectiveness of current efforts and identify opportunities for improvement. Balancing the priorities and needs of an industry as large and geographically diverse as that of California citrus is a challenge, but on this issue the industry is united — we must take every action to stop HLB from spreading.

From growers and shippers to field workers and truck drivers, every level of the industry must work together to stop the ACP and HLB. With harvest season now in full swing and a steady flow of traffic in and out of the field, conditions are ripe for the ACP to spread.

That is why the industry has adopted a train-the-trainer program to educate field crews about best practices to prevent the movement of plant material between harvest sites. This is especially important given the recent detection of HLB in Mexicali, 23 miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border.

California Citrus Mutual and the Citrus Pest and Disease Prevention Program have spearheaded an effort to educate field crews about best practices to prevent the movement of plant material between harvest sites. (Photo Credit: David Eddy)

Training The Trainers

California Citrus Mutual and the Citrus Pest and Disease Prevention Program spearheaded the effort and have so far provided training to nearly 200 individuals who oversee harvesting crews. Similar programs have been developed by other commodity groups dealing with food safety and various regulatory requirements, but none to address an industry-wide threat like ACP and HLB.

Field equipment such as forklifts, ladder trailers, portable restrooms, picking bags, and field bins are continuously transported to groves throughout California and across quarantine boundaries. Packinghouses, growers, and their contractors must take action to ensure this equipment is free of leaves and stems, and consequently ACP, before it leaves the field.

In theory, simple behavior changes such as brushing equipment off at the end of the day or shaking out picking bags can save the California citrus industry. In reality, however, simple behavior changes are never actually simple — not on a $3.3 billion- and 20,000 employees-scale that is the California citrus industry.

We are asking thousands of people to change the way they have done their jobs for decades and it will not happen overnight. But the needle is moving in part due to repetitious training and workshops.

The beauty of the training model is in the delivery. Attendees are shown the direct impacts of HLB with news clips from South America about the devastation the incurable disease has caused their industry and number of jobs lost as a result. They are then asked to participate in a series of activities and demonstrations that propel them to want to adopt the recommended best practices.

Training Can’t Stop There

According to a policy briefing paper recently released by leading researchers at the University of California, Davis and University of California, Riverside, it is clear the pests are being brought to the Central Valley on fruit deliveries from southern and coastal California.

Since HLB was discovered in Florida over a decade ago, California has turned to the growers there for advice on what to do or what not to do to halt HLB. Their message is simple and consistent — stop ACP. California has several advantages over Florida — time being the obvious one.

But, California growers also benefit from geography. There are natural barriers in the Golden State that, all else being equal, are not conducive for ACP to spread north from Southern California. The breaks afforded by Mother Nature, however, are out-powered by human activity.

A map of the ACP detections clearly shows a large proportion of ACP finds occur along major traffic corridors, and recent finds at juice plants in the Central Valley indicate the industry is at least partially responsible for moving ACP.

That is why the industry is and must continue to re-evaluate its farming, harvesting, and packing practices. It’s not easy for an industry to adjust what has been rooted in routine for decades, but the California citrus industry is doing just that in order to preserve its future.

There is still work do be done. In October CDFA detected a breeding population in a potted citrus tree in Placer County that a homeowner brought with him from Southern California. A similar situation occurred recently in Fresno County. These are discouraging reports, but the mere fact that inspectors identified these occurrences is a testament to the strength of the program.

ACP and HLB will have lasting implications on the California citrus industry. The way we do business tomorrow will not be the same as today, nor is today the same as yesterday. It is the industry’s progressive nature, adaptability, and willingness to think outside the “carton” that will save California citrus. ●