How Biofungicides Are Helping Small Fruit Growers Succeed

Timothy Miles speaks well of “soft fungicides” despite any inference that such organic products might actually go easy on varying diseases of small fruit.

“Some people really don’t like that term, but we do use it,” the Extension Specialist from Michigan State University says. “So, I’m going to use it.”

And so, he did at the annual Great Lakes Fruit and Vegetable Expo in Grand Rapids, MI. In the process, blueberry and grape growers, particularly those from Michigan and its surrounding states, left the DeVos Place Convention Center knowing they at least have treatment options.

Softer products (biofungicides), Miles concludes, while generally not as strong as their conventional site-specific fungicide counterparts, can be effective in the treatment of small fruits. The products are most useful, he adds, when incorporated into conventional programs due to the high amounts of fungicide resistance.

“In small-fruit systems, particularly with botrytis and powdery mildew with grape, we have a lot of fungicide-resistance problems, so any new modes of action would be helpful,” Miles says.

Other attributes of softer products, according to Miles, include:

The use of less active ingredients: “You all manage and are good stewards of large swaths of land. That’s a benefit, not having a large amount of active ingredient spread into the environment.”

Novel — but proven — mode of action: “It’s another mode of action that we have spent decades of research on developing.”

Marketing: “A lot of times people might want to advertise that they’re using certain products in their fields.”

Softer products now on the market run a much wider gamut than most growers realize. Miles says these include synthetics, oil products, Bacillus products, and OMRI-listed products.

“Sometimes people wouldn’t put synthetics into this group. I will sometimes,” Miles says. “A good example is the strobulurins. I know they have a lot of fungicide-resistance problems, but they were always considered a reduced-risk pesticide. They’re really active at a low concentration. So, they themselves are probably softer than at least what had been conventionally used.”

CONTROLLING BLUEBERRY DISEASES

In Michigan the focus is on three blueberry diseases — mummy berry, stem blight, and anthracnose — that typically require season-long management, Miles says.

Mummy berry generally starts the management season in the early spring when mummies germinate and develop apothecia, the small, cupped mushroom structures that produce airborne spores. Approximately 40% of all fungicide applications wind up being attributed to the management of the disease, Miles says.

“What we’re really trying to do is get rid of these apothecia. That has downstream effects if you don’t control those because shoots get blighted, and that affects fruiting for next year,” he says.

Mummy berry efficacy trials conducted by Miles in 2022 spoke well of several biological products, including Howler (Pseudomonas chlororaphis, AgBiome Innovations), Serenade (QST 713 strain of Bacillus subtilis, Bayer CropScience), Oso (polyoxin D zinc salt, Certis USA), Double Nickel (Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Certis USA), and LifeGard (Bacillus mycoides, Certis USA).

“The biologicals in some ways looked really similar to the conventional products,” Miles says. “That was exciting to see. We had similar control compared to our control.”

Anthracnose represents the major focus for Miles. The late-season disease is targeted from about bloom all the way up to fruit harvest.

Several biological products may have efficacy against anthracnose, Miles says, based on trials over the years. These include EcoSwing (citrus extract, Gowan), Jet-Ag (peroxyacetic acid, Marrone Bio Innovations), Stargus (Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Marrone Bio Innovations), Oxidate (peroxyacetic acid and hydrogen peroxide, BioSafe Systems), PreVam (citrus oil extract, Oro Agri), Howler, LifeGard, Double Nickel, and Oso.

“I would consider most of them — not entirely — about moderate to good in their efficacy,” he says. “If we get applications on them regularly, around seven to interval, we’ve been getting pretty good control.”

CLUSTER ROTS OF GRAPES

A “bunch of different things” like to rot grapes, Miles says, specifically botrytis, sour rot, Phomopsis, black rot, ripe rot, and bitter rot. Botrytis accounts for about 60% to 70% of grape rotting in Michigan while approximately 30% is attributable to sour rout.

“Grapes are big bags of sugar that hang from the vine for months and months,” he says. “It’s pretty much the perfect environment for these organisms.”

Timing is critical to control grape diseases, Miles says. Specific to botrytis, four spray applications are recommended — at bloom, berry touch/bunch closure, then late season at veraison, and close to fruit ripening.

With a late-season disease such as sour rot, Miles says sprays typically occur at veraison and possibly every seven days all the way to harvest.

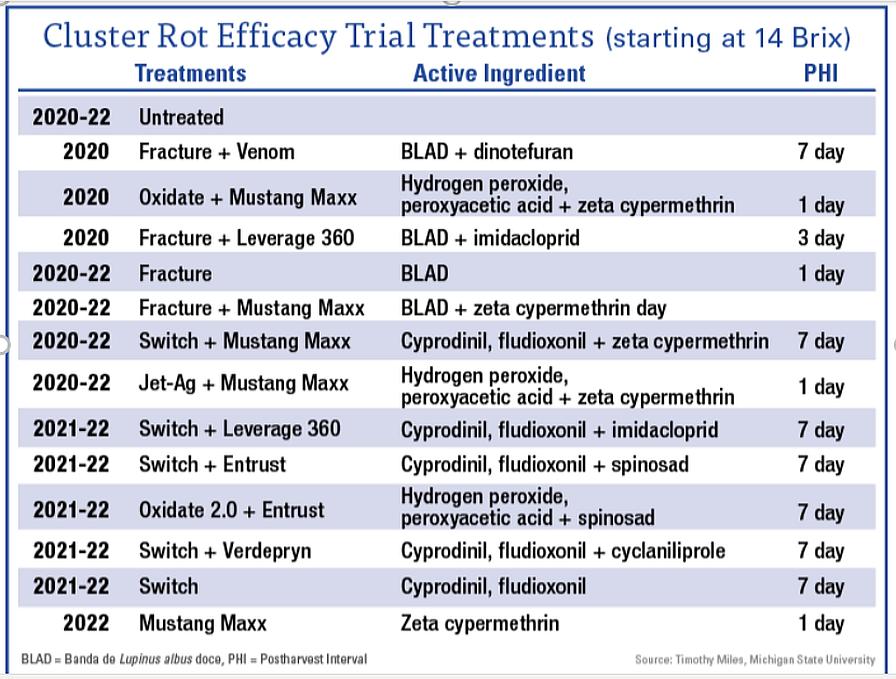

Since 2020, Miles has conducted efficacy trials of various cluster rot treatments, both conventional and biological (see chart below). Typically used has been the biofungicide Fracture (Banda de Lupinus albus doce/BLAD, FMC). Also included have been combinations with insecticides in light of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster being a vector for sour rot.

Graphic courtesy of Timothy Miles

“It was really critical that we have that insecticide in this trial,” Miles says. “Regular fruit flies tend to be a strong vector.”

Overall, the trials have shown that several biologicals are capable of reducing cluster rot.

“Separate trials have also showed that we have some efficacy on some of the biologicals for botrytis, which is really encouraging,” Miles says, “just because botrytis is probably one of the most difficult diseases to manage for biological products, at least in the small-fruit systems I work on.”