Why Disease Control Is More Challenging on Leafy Vegetables

Foliar diseases can have a big impact on vegetables in the field. Even a few small spots make leaves of Portuguese cabbage unmarketable.

Photo by Anthony Keinath

I’ve spent much of my career studying fungicides used against foliar diseases of vegetables. Fungicides are the main method for managing these diseases in conventional agriculture. The old saying fungicides are cheap insurance against disease is still true today.

As all growers know, input costs, including fungicide prices, are up. The increase seems to be more in line with overall inflation than the higher costs of fertilizer and fuel. Nevertheless, it’s a good time to consider how best to use fungicides for not only environmental reasons but economic reasons.

Fruiting Vegetables Tough It Out

A strong case can be made to spray fungicides on vegetable crops when there is a clear relationship between symptoms on the foliage and yield of the crop. One good example from my recent work is downy mildew on slicing cucumber.

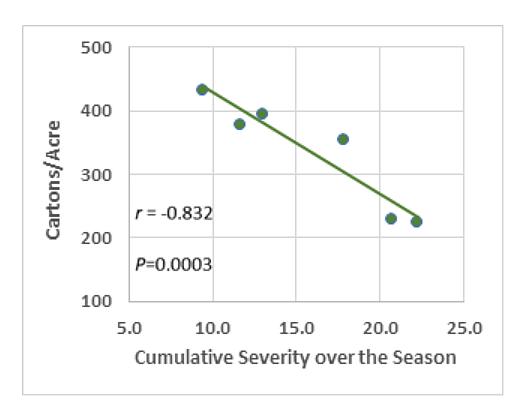

The straight-line graph below with severity of downy mildew on the x-axis and marketable weight on the y-axis clearly shows that reducing severity translates to higher yield — a good payback.

As cumulative severity of downy mildew increases, yields of slicing cucumber decrease.

Notice that with downy mildew and many other foliar cucurbit diseases, the part of the plant sprayed is not the part harvested and eaten. Downy mildew infects the leaves, not the fruit. That said, as downy mildew reduces healthy green leaf area, it also reduces sugar content of melon fruits.

An economic threshold for downy mildew is not a complete absence of symptoms on leaves. In fact, even if 50% to 55% of the foliage on slicing cucumber is diseased by the end of the season, growers can still make a decent profit — $7,200 per acre (based on small plot yields).

Small Infection Rate: Big Impact

The stakes are much higher, however, with leafy greens and herbs. Foliar pathogens grow directly on the part of the crop that’s harvested, sold, and consumed. A much higher level of control is needed to achieve an economic return.

Let’s stay with downy mildews as an example and consider brassica downy mildew on collard.

This disease is one of the “low-severity, high-incidence” diseases that can affect a significant proportion of the leaves (high incidence), but not much leaf area is diseased. Even one spot normally means the leaf is graded out, especially if the collard is being sold, chopped, and bagged.

For example, in a spring field experiment, 75% of young collard leaves had downy mildew, but the diseased area per leaf averaged only 2%. The most effective fungicides prevented downy mildew on 85% to 90% of the mature leaves, meaning only 10% to 15% of the leaves were diseased — a far cry from the 50% diseased leaves tolerated by cucumber.

I’ve observed similar scenarios with Alternaria black spot on kale and Cercospora leaf spot on beet greens or the leaves of bunched beets: large numbers of unmarketable leaves with only a few spots on each leaf.

Older Leaves Most Susceptible

Another shared characteristic among these three diseases is they are found only or mainly on the older leaves. Young leaves may have a bit of natural resistance to infection that declines over time.

Even though we grow them as annuals, collard, kale, and beets are biennials that focus on vegetative growth the first year and flowers the second year. It’s not surprising, then, that the older leaves aren’t meant to last the natural lifespan of the plant.

The plant’s physiology, however, suggests another way to tackle these foliar diseases: harvest as early as possible when spots are limited to the outer or older leaves that can be trimmed off with minimal loss of product.

Trimmings and other cull waste from the packing line should be composted at 150°F for 21 days to eliminate pathogens. If cull waste is returned to the field, follow the recommended rotation interval for the disease in that field — typically two years without a susceptible crop.

The rotation period allows time for infested debris to decompose completely. Since most foliar pathogens aren’t adapted to long-term survival in soil, they are eradicated. Adding a legume cover crop to the rotation will supply nitrogen to microbial decomposers and enhance their activity.

Achieving the high level of disease control necessary to produce blemish-free leafy greens involves diligence and an integrated approach to enhance the activity of foliar fungicides.