More Research Information Needed in Battling Plant Pathogens

Sport coaches, athletes, and their teams all recognize the value of knowing their opponent. Analysis, study, and research on their next opponent, called a scouting report, helps increase the chances of success on the court, field, or arena. In farming, your microscopic “opponents,” pathogens that affect your crops, also are worthy of such analysis. Filling in the blanks gives you the best chance of exploiting pathogen weaknesses and devising the appropriate approach to disease management.

Diagnostics and Etiology: The initial task of the researching plant pathologist is to discover the cause of the issue. Etiology is the study of the causes of a disease, so etiology and diagnostics are closely linked in determining what is behind the crop problem.

Is the culprit a fungus, bacterium, virus, or other microbe? What is the scientific name of the microbe? Is it a pathogen known to infect this crop, or is it new to this plant?

Diagnostics may determine that a pathogen is not involved at all but that an environmental element, production factor, or physiological or genetic phenomenon of the plant is responsible for the symptoms. Without confirmation from etiological research, further studies of the disease or condition will be compromised.

Characterization: Following closely on diagnostics and etiology, pathogen characterization is the area of research that delves deeply into the pathogen’s identity. Knowing the precise genus, species, sub-species, or other taxonomic label of the microbe is essential.

Once an organism name is established, could this pathogen of concern be a new mutant, strain, or race of an already known foe? New strains of rust fungi infecting grain crops could result in significant yield losses. New races of Fusarium wilt pathogens could compromise crops such as celery, lettuce, or tomato.

These days, researchers deploy a broad range of tools to characterize pathogens. Some methods use decades-old approaches such as inoculating a series (differentials) of crop cultivars to see which ones are resistant or susceptible. Using differential cultivars helps pinpoint the development of new races. Newer, DNA-based methods can reveal the identity and variation of the organism at the molecular level, providing clarity on the exact pathogen being studied.

Biology and Life Cycle: How does the pathogen grow and reproduce? How fast does it increase? What is the mechanism by which the pathogen grows and survives? What specialized survival or dispersal structures does it make?

Is the life cycle relatively simple, such as that of powdery mildew on strawberry, in which the fungus generally only makes mycelium on leaves, followed by the formation of spores, spores that detach and land on leaves and make more mycelium?

Or is the life cycle more involved, such as the biology of the clubroot pathogen of crucifers? The Plasmodiophora clubroot fungus has a complicated cycle of resting spores, multiple types of swimming spores, and plasmodia (intracellular bodies inside roots).

Life cycles can involve other, non-pathogen life forms as well. The damaging Impatiens necrotic spot disease (INSV) on lettuce is caused by a virus the thrips insect carries between plants. Understanding the life cycle of this INSV pathogen therefore requires knowing the life cycle of its insect vector.

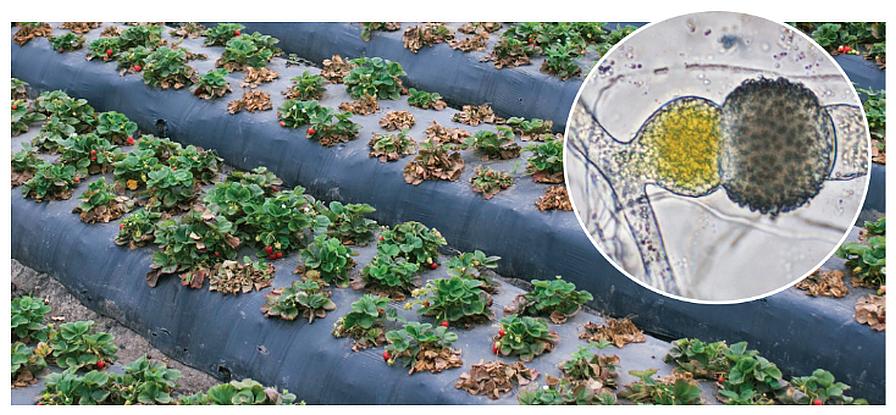

Epidemiology is the research area that determines how a pathogen spreads through a crop, field, and region. (Inset) Diagnostics and etiology are the research-based components that initially identify whether the pathogen is a fungus (pictured), bacterium, virus, or other entity.

Photos by Steven T. Koike, TriCal Diagnostics

Epidemiology: Once you understand pathogen life cycles, you can explore the broader topic of epidemiology, which outlines how a pathogen, and the subsequent disease, spreads and moves in the environment. This research area develops information on how the pathogen and disease become distributed and to what degree (often referred to as incidence).

Epidemiology research is key to understanding the mechanisms, factors, and conditions that account for how pathogens become damaging in a single field, ranch, and even region.

For example, researchers have documented how the late blight disease of celery is spread and develops via a combination of infested seed, splashing water, and diseased celery crop residues. Downy mildew diseases depend on wind-borne spores, the presence of susceptible crops, and requisite hours of moisture on leaf surfaces. Verticillium wilt of vegetable crops may be seedborne in some crops but is mostly spread via long lasting survival structures (microsclerotia) embedded in infested soil.

Management and Control: Once the blanks have been filled in for the etiology of the disease, precise characterization of the pathogen, biology, and life cycles of the organisms involved — and the epidemiological mechanism of pathogen and disease spread — the researcher, in collaboration with other agricultural professionals, can fashion the most effective integrated disease management strategies. Such a strategy will rely on this detailed information, a scouting report, of the microbial opponent, thereby increasing the chances of realizing successful crop yields and quality.