Drought’s Double-Edge Sword: Can It Put a Damper on Plant Disease?

Dry weather patterns and significantly reduced rainfall in the West have, of course, attracted many headlines and much attention. As we ease into the autumn season and then into perhaps another winter without much precipitation, the impacts of limited rain are well known.

The drought has a role in the environmentally and socially catastrophic forest and wildland fires that dot the western states.

Agriculturally, without consistent annual rains to restore surface reservoirs and groundwater, there are lasting impacts to western farmers because of restrictions on irrigation water. Some annual crops are not being planted due to such limitations, while some perennial tree and vine crops are being ripped out due to water shortages.

In all ecosystems there are few organisms that are unaffected by lack of rain. Interestingly, even the pathogenic organisms that cause disease on our crops are influenced by precipitation shortages. Many important, damaging diseases of crops are strongly driven and dependent on the splashing water and prolonged moisture that rains provide.

Bacterial Disease Rely on Rainfall

Bacterial plant pathogens such as Erwinia, Pseudomonas, and Xanthomonas are microscopic, single-celled organisms that cannot spread between plants without help from other factors. Once a plant pathogenic bacterium has infected a host plant, the active bacteria will remain only on that individual plant unless something moves them. The main way bacteria are moved is through splashing water. Rains are therefore critical enablers that splash bacteria from one infected leaf to another leaf, and from a diseased plant to an adjacent healthy one. Rains and the extended wetness they provide also activate bacterial pathogens. If conditions are dry, bacteria become inactive and transform into dry, scaly deposits that stick harmlessly to plant surfaces.

Droplets of bacteria can ooze to the surfaces of infected plants but require splashing rains to be dispersed to adjacent plants.

Photo by Steven T. Koike

Dry winter conditions can significantly reduce bacterial diseases on perennial crops. Bacterial canker of stone fruit trees becomes less of a factor for growers of peach, nectarine, and almond trees. Bacterial blast and fire blight pathogens of apple and pear do not spread extensively during the winter if rain is not in the forecast, though the fire blight pathogen can be spread in the spring via bees and other insect carriers.

No Rain Suppresses Even Seedborne Diseases

Vegetable crops are subject to several bacterial pathogens that are seedborne and infect the individual seedling that grows from the infected seed. Without splashing water, however, those bacterial pathogens would remain with that one plant and not spread to others.

Rains are, therefore, key factors in establishing winter and early spring outbreaks of these problems. Broccoli, cauliflower, and other crucifer crops are hosts of three bacterial pathogens, two of which (bacterial leaf spot and black rot) can cause significant damage. Dry winters will inhibit development of these two issues. Seedborne Xanthomonas causes bacterial leaf spot of lettuce. Drip-irrigated lettuce, grown in the era of limited spring rainfall, will hardly show this disease even if the crop is grown from infested seed.

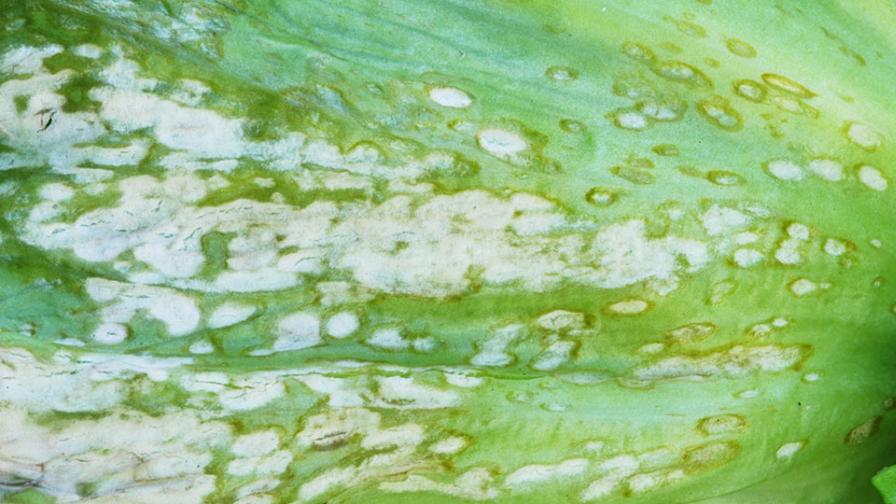

The white spores of the anthracnose fungus will not be seen on lettuce if there are no spring rains.

Photo by Steven T. Koike

Fungus Reduced in Droughts

Fungal plant pathogens, generally, are also passive regarding movement from plant to plant. This is especially true of foliar pathogens, which are dependent on winds and rains to disseminate the spore inoculum. Some spore types are readily dispersed by winds, so these spores will spread regardless of weather patterns. However, other spore types need to be splashed around by water and, similar to the bacterial pathogens, are very dependent on rains. Shot hole and leaf curl diseases of Prunus tree crops are less frequently encountered if the winter/spring weather is dry.

The lettuce anthracnose pathogen resides in the soil and requires splashing water to propel inoculum onto lettuce leaves, and cool wet weather is needed to facilitate infection. During these drought seasons, lettuce anthracnose has become a very rare disease. Rust diseases on vegetable crops are also significantly reduced in rainless periods, even though rust spores are spread miles by winds and do not depend on rains for dissemination. Rather, dry winters and springs retard infection and disease development of rust, even though rust spores are present. Recent dry springs have reduced the amount and severity of garlic rust, for example.

Even though limited rainfall in the West can result in fewer crop disease concerns, one hardly wishes for the drought to continue. Ample rainfall is critically important in so many ways for environmental, ecological, economical, and social reasons. However, it is good to be informed about how all these agricultural and biological systems are integrated and influenced by weather and environment. Our crops need the rain. So do the plant pathogens.