Why Agriculture in the Golden State Is Going Biological

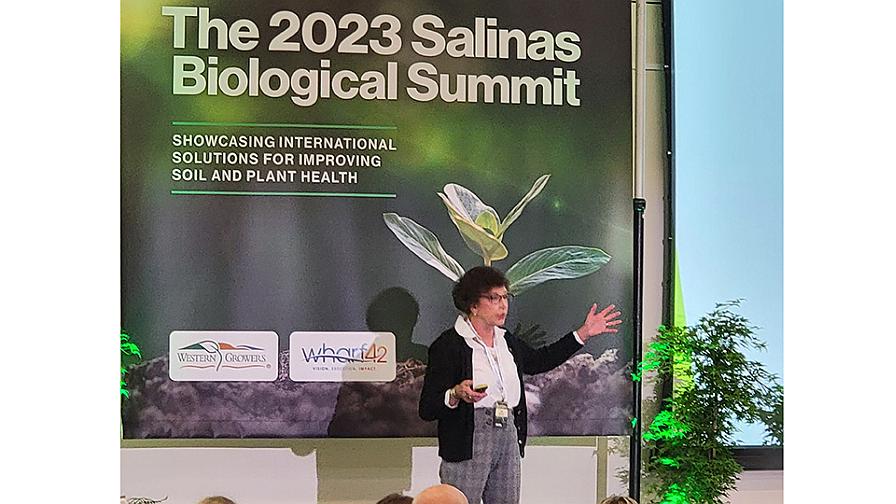

Pam Marrone, one of 33 people on the committee appointed by the Department of Pesticide Regulation to draft the Sustainable Roadmap, addresses the standing-room-only audience at the 2023 Salinas Biological Summit.

Photo by David Eddy

A plan issued by the California Department of Pest Regulation (DPR), which didn’t attract much attention when it was passed earlier this year, was the hot topic at Western Growers’ 2023 Salinas Biological Summit.

Sustainable Pest Management: A Roadmap for California calls for wholesale change to the state’s approach to pest management over the next 25 years. It’s likely to have global ramifications, as the approach is nearly as comprehensive as the European Union’s (EU) Green Deal, a plan to have 25% of EU agricultural land be organically farmed by 2030.

The California strategy contains no similar organic mandates, but because about half the nation’s fruits, nuts, and vegetables are farmed in the Golden State, the Roadmap’s effects will no doubt reverberate across the country. Some chemicals for specialty crops have limited use in the big government-subsidized program crops that account for much of the nation’s cropland, such as corn and soybeans.

Sustainable Pest Management: A Roadmap for California has two stated goals, both to be achieved by 2050. The first: California has eliminated the use of priority pesticides by transitioning to sustainable pest management practices. The second: Sustainable pest management has been adopted as the de facto pest management system in California.

DPR Director Julie Henderson was among the speakers at the June inaugural event who addressed the sweeping initiative. She told the 350 attendees, including growers, representatives from biological companies — from start-ups to the biggest chemical firms, nearly all of which have acquired biological companies to get an immediate toe hold in the growing market — that 25-plus years are necessary to implement it.

“We need the time, there’s no quick fix here,” she says. “We need to consider the hazard of not giving farmers alternatives [to chemicals].”

Henderson promised the audience — which was much larger than anticipated, as two overflow rooms at the Salinas Civic Center were used to show video of the proceedings — that all the state’s growers will have access to all the details of the state’s new Sustainable Pest Management (SPM, as opposed to the current IPM) by 2030.

The difference between the two is that in IPM, the grower waits until pests get to serious levels before reacting by using a pesticide, whereas SPM takes a much more active, preventative approach. That is largely a function of how biological products work, as they must be applied well before pest problems emerge, much less serious ones, says biologist Pam Marrone, who served on the Roadmap committee.

Marrone was one of 33 people on the DPR-appointed committee representing a variety of interests, from pesticide manufacturers to environmental activists. Marrone is the Co-founder of the Invasive Species Corporation in Davis, CA. She notes that a bone of contention is likely to be what chemicals will be designated “Priority Pesticides,” meaning it’s a priority to limit their usage. They are the more toxic pesticides, but what actually makes the list remains to be seen. A list will be drafted, Henderson says, by another committee appointed by DPR.

“We need lots of stakeholders on the committee developing the list,” she says.

Marrone says it’s understandable many growers don’t know enough about biologicals because the people they look to for answers, mainly pest control advisers (PCAs) and university Extension agents, are themselves not well-informed. PCAs haven’t really had an incentive, Marrone says, noting there are no Continuing Education Units offered for sustainability.

The Salinas Biological Summit might seem like an odd endeavor for a conservative group like Western Growers, but President and CEO Dave Puglia says in introducing the program that it was logical. Nearly a decade ago, they launched the Western Growers Center for Innovation and Technology in Salinas after realizing start-up companies’ technology could be a real boon to their members, who are vegetable, fruit, and nut growers in California and Arizona.

“We need to pivot, we need to adapt, it’s another good example of cooperating, like with tech,” he says. “Cooperate — don’t fight.”

Cooperation is crucial, agreed the state’s Department of Food and Agriculture Secretary, Karen Ross. She says it was logical to launch such a project in the state for a couple of reasons. First, California has already been signing agreements with other countries over climate change, forming partnerships. Second, California has unparalleled access to a lot of venture capital.

“We need capital to sustain this journey,” she says.