How to Predict Bitter Pit in Honeycrisp Apples

When it comes to managing bitter pit (BP) in ‘Honeycrisp’ apples — arguably the most susceptible variety to this devastating disease — you need to consider many factors. Since you’ll only be able to see BP symptoms after the fruits have come up from long-term cold storage, you face the puzzling dilemma of whether you should sell the apples right after harvest or take the risk of putting them in storage.

A group of researchers from Penn State University, led by Dr. Rich Marini, Professor of Horticulture in the Department of Plant Science, recently developed a predictive model that will hopefully help, not so much to manage the disease but to predict BP potential — and assist apple growers with their marketing strategy.

The new predictive model developed at Penn State Extension is based on two variables, shoot length and the nitrogen to calcium ratio (N/Ca), a thorough statistical approach and an innovative sampling method.

This model cuts through many of the complex methods previously used. Until now, you needed to track excessive tree vigor, lower soil pH, hot weather, drought stress, large fruit combined with low crop loads, early harvest, and the nutrient balance within the fruit. It made for an arduous task — there are too many variables involved.

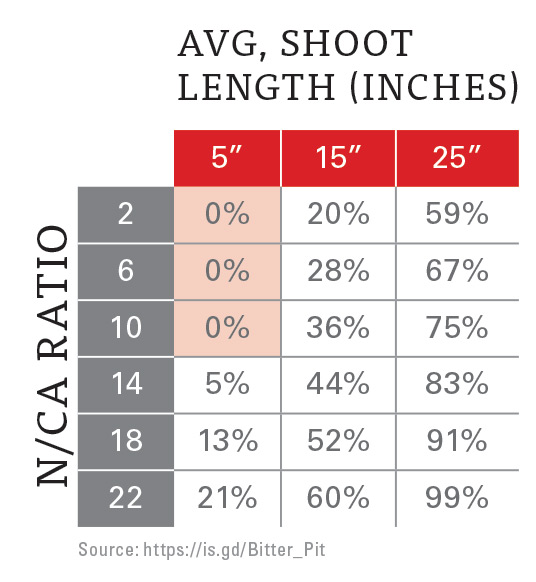

Estimated percent of apples on ‘Honeycrisp’ trees developing Bitter Pit after cold storage as affected by shoot length and N/Ca ratio. (Source: Penn State University)

The Two-Variable Model

Previous research conducted on several apple varieties had already tied BP to a nutrient imbalance. The existing, predictive models used

this factor with mixed results, so the Penn State research team members decided to introduce a new variable into their model.

“What made our model a little bit different is that shoot length seems to be an important variable to consider,” says Marini. “None of the other models even considered shoot length, an indicator of the vigor of the tree.”

After three years of gathering statistical data, Marini’s team was able to combine the two variables — Nitrogen (N)/Calcium (Ca) ratio and average shoot length — in a simple table that may help apple growers predict the chances of developing BP. For instance, a combination of a N/Ca ratio of 2 to 10 and an average shoot length of 5 inches or less is supposed to reduce the occurrence of BP to 0%.

But a high concentration of N and longer shoot length could increase the chances of developing BP to more than 90%.

Peel Samples: Simple & Accurate

Aside from the shoot length variable and the systematic statistical method used by the Penn State team, a new sampling system was developed to gather data. The researchers decided to analyze peel tissue instead of the traditional flesh tissue.

The tissue samples must be dried before grinding in order to analyze them in the lab. Marini explains that because of the high concentration of sugar in the fruit, the dried flesh is going to absorb water from the air, thus turning it into a toffee consistency that’s very hard to grind. “But if you can scrape all the flesh from the peel, you can grind it like a dried leaf,” he says.

The peel tissue samples must be taken three weeks before the expected harvest date and sent to the Agricultural Analytical Lab at Penn State.

“We should be able to get the results back to the growers before they start picking, so they have time to make a decision about whether or not to store the fruit,” Marini says.

Once the apple tissue is analyzed, the lab sends the results to the grower with a copy to Marini so he can contact the growers to help them interpret the results.

Balancing the Variables

Given the relevance of the study’s two variables, Marini believes more can be done to control the occurrence of BP.

Since shoot length is related to the vigor of the tree, the right pruning may help; however, you may want to consider avoiding soils that are too fertile as well as modifying your fertilizer practices to maintain the adequate N/Ca ratio for ‘Honeycrisp’ sports.

“If the Ca levels are too low in the fruit, we need to spray more Ca. We found that a lot of times growers are not applying enough Ca,” Marini says.

Because calcium is not a very mobile element, it might not get to the fruit when applied to the roots, so growers must apply it directly to the fruit with the right amount of water.

“If you use a low-volume spray, you may not get enough coverage. You have to spray enough so it lands on the fruit and it’s absorbed by the fruit,” Marini advises.

Marini says growers must be careful when using some Ca products in the market. They must be able to determine exactly how much calcium they are applying.

“They have to follow label rate by law, but if they are not putting enough Ca with that particular product, then maybe they should consider a different product,” he says.

Marini recommends using a minimum of 11 pounds of actual Ca — not a Ca-based product — per acre per year divided in six to eight applications.

Worth the Effort

The Penn State Predictive Model was first published in September 2017, too late for Pennsylvania growers to use at harvest so this fall will be the first time the model can be tested in the field.

It’s still unknown whether the model will work in other parts of the country. However, Marini says that a couple samples from Maine were received and analyzed. The model predicted a low incidence of BP, which was accurate, according to the growers. This is too small of a sample to draw any favorable conclusions but still encouraging.

Another area Marini would like to research is the best way to sample an orchard — how many fruits per tree and how many trees per acre. The team had to make do this year without research, using reasonable guidelines, which they published in their production guide.

Marini dismisses the cost of sampling for BP and says it’s cost effective.

“A sample is about $16, so if you have 19% BP and pick 600 bushels per acre, that’s a lot more than $16. It’s worth doing it,” he says.

Marini concludes that the model they developed “only explains about 70% of the variations, so it’s as good as any model that’s ever been published.”

This season is key for Pennsylvania apple growers testing this new predictive model. In any case, growers should follow the production guidelines in terms of balancing the nutrients (N/Ca), controlling the vigor (shoot length) of the ‘Honeycrisp’ trees, and planning sites for future orchards.