California Winegrape Supply Stabilizes

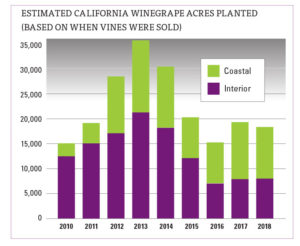

California winegrape growers have largely been planting only at attrition rates for the past few years, and at least one industry expert expects more of the same for 2018.

Jeff Bitter, vice president of Allied Grape Growers, a grower-owned winegrape marketing association, delivered that message to a standing-room-only audience at the Unified Wine & Grape Symposium’s signature “State of the Industry” session in late January.

“Basically, we’re not putting in more vineyards than we’re taking out,” Bitter said in an interview later. “We’re seeing a stable wine environment, as overall wine shipments are not increasing. There just hasn’t been the consumer pull-through to encourage plantings across the industry.”

“Basically, we’re not putting in more vineyards than we’re taking out,” Bitter said in an interview later. “We’re seeing a stable wine environment, as overall wine shipments are not increasing. There just hasn’t been the consumer pull-through to encourage plantings across the industry.”

However, Bitter hastens to add that this steady-as-she-goes forecast is for the industry overall. At certain price points there is real optimism. For example, ultra-premium ‘Cabernet Sauvignon,’ at about $50 per bottle and up, is selling. There is more demand than supply.

But Bitter notes there are only limited areas in Napa and Sonoma to produce those ultra-premiums. The only way to increase production is to increase density, which will definitely be done, and in fact already is being done in many areas of the country that can produce top-dollar fruit.

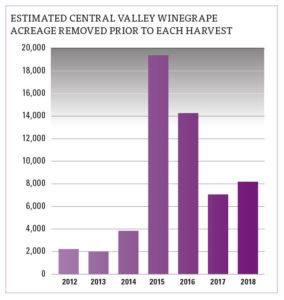

The news isn’t so favorable at the other end of the scale. Bitter is forecasting that even more acres of winegrapes will come out of the Central Valley, where wines of less than $5 are produced, in 2018 than last year.

“There’s just been an ongoing realization among Central Valley grape growers that there isn’t the demand for their grapes. We’re going on four to five years of a lackluster wine grape market. Sometimes it takes a few years for a guy to wake up,” he says. “But it’s not all about the winegrapes. It’s because almonds and other crops are going in instead.”

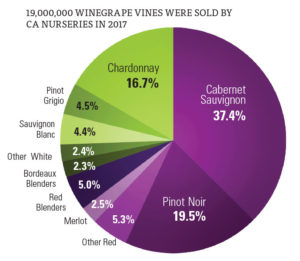

Statewide, in terms of production, red winegrapes continued to be favored by a huge margin over whites, says Bitter. The top white, ‘Chardonnay,’ is a mixed bag. ‘Chardonnay,’ along with ‘Pinot Grigio,’ are the third and fourth most popular varieties in the state.

“We anticipate growth for both, but it depends on the region as to how much growth,” he says. “For example, it’s hard to grow ‘Pinot Grigio’ in a lot of places.”

“We anticipate growth for both, but it depends on the region as to how much growth,” he says. “For example, it’s hard to grow ‘Pinot Grigio’ in a lot of places.”

When it comes to red varietals, the two hottest, and the two most popular overall in the state, are ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Pinot Noir.’ Bitter says the big loser, by far, is somewhat of a surprise because it wasn’t too many years ago that it was proposed as the California State winegrape: ‘Zinfandel.’

“In every region, which is unusual, Zin is down; consumers are not asking for more Zin at all, so growers not only won’t plant more, Zin is coming out,” he says. “Consumers are hot on Cab, ‘Pinot (Noir)’ and red blends, and that’s what will go in instead.”

As for Bitter’s chief take-away messages for growers, let’s break it down by region, though it can also be delineated by price points.

Central Valley

Growers are increasingly narrowing their focus on growing varieties that are well-suited for the area. They are no longer chasing varietal trends, which in past years could get them in a bit of trouble, says Bitter.

For example, ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grapes like the valley heat just fine, but without the huge diurnal temperature swings found in regions like Napa and Sonoma, it’s almost impossible to produce the ultra-premium ‘Cabs’ that are much sought after by wealthy consumers.

“Just because ‘Pinot (Noir)’ and ‘Cab’ are hot, doesn’t mean Central Valley growers should be planting them in a hot weather climate,” he says.

North Valley

There’s nothing that can’t be grown in the Lodi region, says Bitter. It can be nearly as hot as the Central Valley, but because of the cooling influence of the Sacramento Delta, there’s a place to grow almost everything.

“They are in the middle — they can enjoy the top end and the bottom,” he says. “If the economy tanks, they can grow lower-priced wines that don’t pencil out on the North Coast. They are in a unique position, in my opinion.”

But that’s the good news. The bad news, as mentioned above, is that ‘Zinfandel’ seems to be rapidly falling out of favor with consumers. If ‘Zinfandel’ has a home turf in the Golden State, it’s Lodi. But as Bitter says, at least the growers have a lot of options in terms of other varietals.

Coastal California

This region used to be broken out as the Central Coast, but some ultra-premium wines are being produced on the Central Coast, from Santa Barbara and up into Monterey County. Bitter is referring more to a price point, $10 to $20 bottles. This is perhaps the one price point that will see new acres being planted.

“Nearly all the new planting activity is in that price range, that $10 to $20 segment,” he says. “But it’s not out of balance. We’re seeing increased interest in those wines by consumers, so some new planting is warranted.”

North Coast

The North Coast was the common term for the nation’s most well-known wine production region, Napa and Sonoma counties. However, Bitter notes it’s a bit of a misnomer because some of the wines produced in counties even farther north, such as Mendocino, would be more logically placed in the Coastal California category.

Bitter places Napa/Sonoma wines in the “Luxury” category, with bottles fetching more than $20 per bottle. While there is plenty of demand for such wines, ramping up production is not easy. There simply aren’t a lot of acres left to plant in Napa, for example.

“They will see increased productivity, not increased acreage.”

But while all looks rosy in terms of sales projections for these most expensive wines, Bitter adds that this also the segment of the business that hurts most when the economy goes south.

“Consumers will rapidly trade down; it’s happened in every recession,” he says. “History says (these wines) will be affected almost immediately.”

Statewide, Bitter doesn’t expect any real growth in bearing acreage, not just in 2018, but through 2020. Supply will only increase though greater productivity and larger annual crops as dictated by Mother Nature. He adds that caveat because California hasn’t had what could be called a large winegrape crop in the past five years, a streak growers shouldn’t anticipate continuing.

“2013 was the last above average crop, and they’ve even been lower than average, so don’t get used to the crop sizes we’ve had,” he says. “We could return to normal, or go above. Even without increased acreage, if all the acreage produces to its max potential, supply would increase to 4.25 million tons, which would be the all-time high.”