Precision Irrigation Helping Save Precious Resource for This California Vineyard

Jonathan Walters knows he’s lucky as a grower, being able to farm 500 acres of vineyard at a high elevation above a scenic lake in Northern California. The General Manager of Brassfield Estate Winery in Clearlake Oaks also knows he’s facing difficulties, as the vineyards are on steep slopes, have a wide variety of soils, and include a total of 18 wine grape varieties.

“It’s both a blessing and a curse — more of a challenge, really,” he says, gazing at the tremendous views above Clear Lake.

Located northeast of San Francisco, Clear Lake is the largest natural lake in California, stretching for nearly 20 miles parallel to the Pacific Ocean, about 40 miles away. The winery sits on rolling hills covering a total of 5,000 acres, with the rest of the land to remain natural, as the owner wishes.

The land is located in the High Valley American Viticultural Area (AVA). This is a highly unusual AVA in that it’s located in a transverse valley, which, unlike most valleys, has an east/west orientation and is a big advantage in producing great fruit because of its effect on the winery’s conditions.

Walters says that during most of the growing season, the state’s Central Valley gets hot, routinely in the ’90s in the afternoons, and that pulls the breeze coming from the ocean to the west across the vineyards.

“It’s like a giant air conditioner gets turned on every day,” he says, smiling.

Besides the climate, Walters feels fortunate to farm at high elevation, because the wide temperature swings can produce finer quality grapes. He says only an estimated 1% of wine grapes worldwide are grown above 1,000 feet in elevation, and the valley floor where he farms sits at 1,800 feet. They grow grapes as high as 3,000 feet, one 6.44-acre planting of ‘Syrah’ and ’Viognier’ grapes.

“One percent is not a lot, and almost all of the grapes we grow are over 2,000 feet,” he says. “I think that makes us very special.”

STEEP SLOPES

Just because they are blessed with such a beautiful place to farm in such a conducive climate doesn’t make the farming easier. For example, they do farm on a lot of slopes. Just 220 of their 500 acres are on the valley floor. They farm this acreage very differently. For example, weeds are taken care of with an under-vine cultivator, and no herbicides are used, enabling the winery to be certified sustainable by the state.

“On the slopes, we can’t till because there might be too much erosion, especially if we see storms like we have in the past few weeks,” he says, referring to the January storms that slammed the state, bringing a year’s worth of rainfall to many locations in just a couple weeks.

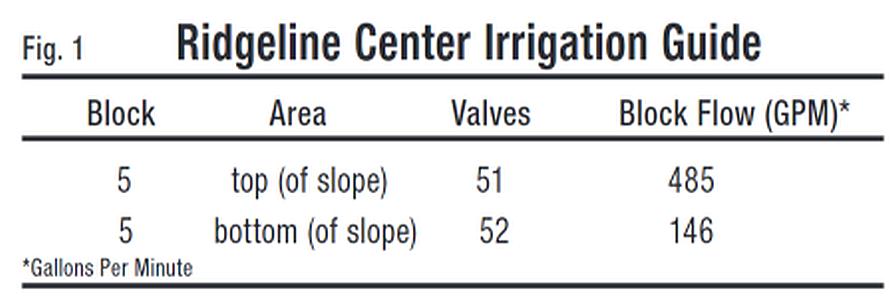

The steep slopes mean the vines’ irrigation needs vary widely. It’s not unusual for the vines at the top of a given block to need three times as much water as the vines at the bottom of that same block, such as in the excerpt from the Ridgeline Center Guide chart (see Fig. 1 in the photo slideshow above).

Walters tackles the needed variation with a Netafim system that boasts a controller and solenoid valves in the field. The system allows Walters to precisely control the amount of water applied at the same time he’s mixing in various inputs — “micro-dosing the vines,” as he puts it.

It requires a lot of water on hand, so Walters has two 10,000-gallon tanks that are constantly being filled from a 100-acre-foot reservoir that Brassfield installed, which is nearly a mile away. The extensive system means they have a total of 20 miles of pipe in the ground.

The system is incredibly sophisticated, with valves turning on and off automatically as required. The system is so efficient that if an emitter falls off, it can compensate for the lost pressure. Some would say it’s an excellent example of precision agriculture, though Walters has a slightly different viewpoint.

“It’s precision, and it’s efficiency,” he says. “To me, to be precise, you have to be efficient.”