How International Fruit Genetics Is Taking Plant Breeding To the Next Level

Building a campus for fruit breeding is not only a practical move for International Fruit Genetics (IFG), it’s an appropriate metaphor for what’s happening in the world of fruit breeding: More fruit varieties are being developed in the private sector. Traditionally a province of Land Grant universities — think the ‘Honeycrisp’ apple, developed at the University of Minnesota — as money has dried up for these universities’ Extension programs. Breeding is not the priority it once was.

But an even more important factor, says John Clark, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of Arkansas and one of the most decorated breeders in the country, is that private breeding in fruit has proved economically feasible. It’s a logical extension of private breeding, as first it was row crops, because of the tremendous acreage, then vegetables followed. Fruits are now taking a similar path. It really started with Floyd Zaiger (who developed the Pluot, among other fruits), and his mentor Fred Anderson (the father of the nectarine), Clark, an American Fruit Grower columnist, says.

“But really it was one man – Floyd Zaiger, who we would all credit as a visionary, who made the industry aware of the possibilities,” Clark declares.

David Cain, a grape breeder with Sun World in the 1990s, shared Zaiger’s spirit, Clark says. He had the vision to create International Fruit Genetics, which was founded in 2001 with investors Sunridge Nursery, which is owned by the Stoller family, and industry legend Jack Pandol. (IFG was bought by the Spanish company AM FRESH Group in March, which announced it was merging IFG with Special New Fruit Licensing.).

Cain, now retired, worked with Clark on introducing the genetic diversity from University of Arkansas ‘Muscadine’ grapes into the grapes he was developing. One such variety would become the aptly named ‘Cotton Candy’, a big success. Though the world’s top seller is a variety of green grape — which is more popular and familiar to consumers — ‘Sweet Globe’, also produced by IFG.

“David had the vision. He knew the genetic potential was there,” Clark says. “David had that vision, just like Floyd Zaiger had that vision: ‘I can produce this, and the market will love it.’”

Andy Higgins, who took over as CEO of International Fruit Genetics in 2017, says there is no doubt Cain made the difference. Cain, who developed the aforementioned ‘Sweet Globe’ and an astounding 65 other table grape varieties, realized they had the capability to produce far more flavorful grapes than were currently available, and people would love them. According to Higgins, “Dr. David Cain flipped everything on its head by saying: ‘Let’s start with the consumer. Fruit should taste good. We should inspire the consumer to try more.’”

Cain’s pursuit seems obvious now, but that’s a far different approach than that taken traditionally by public breeders. Higgins says during the heyday of public breeding, in the 1960s and up into the early ‘80s, the universities were addressing specific industry challenges. Indeed, he notes the University of Minnesota is now focusing on controlling powdery mildew in grapes.

“It makes sense they’re breeding for farmers, not consumers,” he Higgins says. “But our whole focus is to inspire the consumer. The berry industry, companies like Driscoll’s, set an excellent example. Fresh, consistent, in a clamshell 52 weeks of the year. Berries were very seasonal, and Driscoll’s transformed the industry.”

Berries are an excellent example of how private breeders, such as Driscoll’s and Fall Creek Nursery, can transform an industry. Though public universities are still responsible for many mainstay varieties, a lot of the newest, sweetest, crunchiest varieties come from private breeders. They have the ability to control these varieties, which goes far beyond that of public breeders, Higgins says, and IFG is taking the lead.

“We’re the only breeder in this space to devote lots of money to quality assurance,” Higgins says. “‘Cotton Candy’, for example, cannot be sold with a Brix of less than 19, and it has to taste like ‘Cotton Candy.’ We want to make sure that if the sign says ‘Cotton Candy’, it tastes like ‘Cotton Candy’.”

Ensuring varieties are correctly displayed and sold warrants an approach worthy of a TV crime show spinoff: “CSI: Fruit.” IFG hires so-called “blind shoppers” wherever their varieties are sold around the world, and the shopper buys ‘Cotton Candy’, for example, just like any other consumer. But instead of being eaten, the grapes ship to a lab for DNA testing to see if it’s actually ‘Cotton Candy’. If not, IFG contacts the retailer, which Higgins says happens more frequently than he’d like, especially with formerly generic packaging. But if they don’t get cooperation, IFG will contact the authorities, and violators have been prosecuted.

OTHER DIFFERENCES

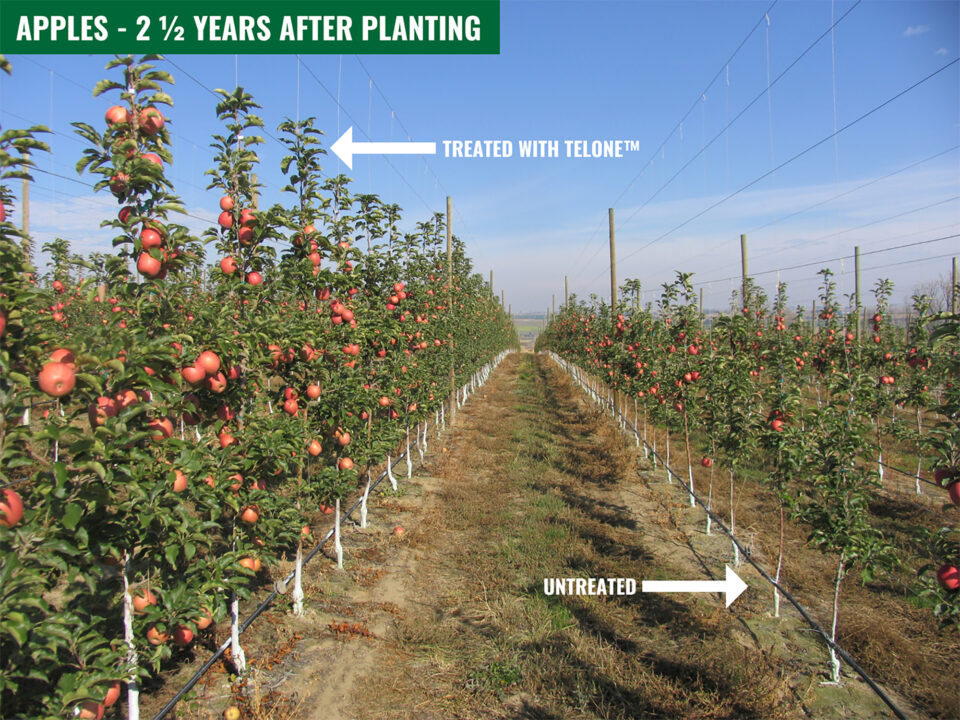

Make no mistake, focusing on the consumer certainly doesn’t mean neglecting the grower. Far from it, as breeding for the most flavorful varieties is just the first step, though it is time consuming. International Fruit Genetics develops 20,000 seedlings a year, and of those maybe 30 to 40 make it to trials, and usually only one makes the cut. It generally takes 15 years from crossbreeding to commercial variety — IFG is demanding, and any minor defect disqualifies the variety — but it all depends on the type of fruit. After that, what they do at IFG is try to view everything through the grower’s eyes, “a filter we’re always using,” Higgins says, noting that historically, breeding was not just the first step, but the only step.

“In the usual system, both public and private breeders would say ‘Here you go’ to the grower and just walk away,” he says. “But this is such a long-term investment, and we’ll be there with them. It also makes it possible for us to see the varieties in use. It allows us to learn.”

The IFG system is vastly different, and the key to that distinction is it’s based on an entirely different premise, Higgins says. IFG doesn’t sell the vines at all. After growers agree to buy them, they pay a licensing fee, then pay a certain additional amount each year based on their sales.

“We don’t sell anything — we essentially just rent plants to growers,” he says. “In our model of renting varieties, we get paid just like the farmer — a percentage of the FOB (free on board). We rise and fall with the success of our growers.”

One interesting development on the public/private breeding scene is that the new IFG campus being built in McFarland, CA, just north of Bakersfield, will be the only such fruit breeding operation in the U.S. that will have a permit to ship direct from USDA, Higgins says. Completion is expected in August 2023, and features a pathology lab, because all plants have to be free from viruses, as well as a chemistry lab full of test tubes for marker-assisted breeding — not genetic modification, he emphasizes — where seedlings are screened.

The buildings on campus feature windows wherever feasible to show the scientists working, an effort Higgins calls “Science on display — you can see what’s going on in each lab anytime.”

The windows also are designed to make the new IFG facility an enjoyable place to work. Indeed, coupled with all the free areas intended to foster communication, the motivation is to generate synergy among Lead Plant Breeder Dr. Chris Owens and the scientists in the many requisite disciplines, including chemistry, biology, pathology, and genetics.

“We wanted a collaborative balance to attract top talent,” Higgins says, who adds they are now hiring in all of these fields.

CHERRY ON TOP

The other fruit IFG has gone into in a big way is sweet cherries. The company now has 48 table grape varieties and 10 sweet cherry varieties, and growers can expect to see innovation in sweet cherries too, Higgins says.

“We’re at the same spot where we were with grapes in 2012,” he says, adding with a smile. “We’re on our great grandchildren in grapes, but just the kids in cherries.”

Because it’s a tree fruit, the development cycle is much longer than for a vine crop like grapes. But they may be worth waiting for, particularly if you are trying to grow cherries in areas like the south end of the San Joaquin Valley, right where IFG is located. In recent years, growers have complained of the impact of climate change, from late frosts to early hail to late rain, and a simple lack of consistent weather. But the biggest problem is the lack of chilling hours, and that’s where the folks at International Fruit Genetics are focused.

“One hundred percent of the cherry varieties they are working on are harvested early and low-chill,” Higgins says. “Ordinary chilling hours for cherries is 800 hours or more, and IFG’s needs a max of 300 hours, and several varieties require just 150 hours.”