New Research Looks at Sustainable Spotted Wing Drosophila Controls

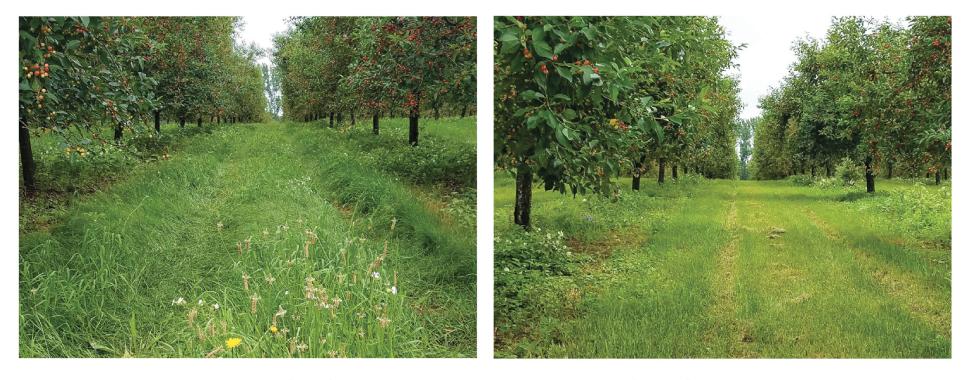

Bi-weekly mow treatment (left) and standard mow treatment (right) in mid-July, 2018. (Photos: MSU Extension)

Spotted wing drosophila (SWD) is a picky pest, waiting for just the right weather conditions and fruit ripeness to lay eggs in fruit. As the flies’ eggs hatch, larvae feed inside the fruit, causing it to rot. Some heavily infested orchards even produce a fermentation-like odor over time.

These tiny flies love small fruits such as blueberries, strawberries, raspberries, and cherries. Northwestern Michigan grows 50% of the country’s tart cherries and battles with this now key invasive pest. Keeping SWD under control is difficult because they reproduce as often as every seven days, resulting in rapid population growth.

“It’s been stressful for growers and researchers to find answers,” says Nikki Rothwell, Coordinator of Michigan State University’s Northwest Michigan Horticultural Research Center. “It’s kind of a race against time because you have to get to these guys before the populations build or you don’t really have a good chance of beating them.”

Rothwell and Research Technologist Karen Powers have been studying SWD’s environmental preferences and various farm management techniques as a more holistic approach to keep pest populations under control.

Catching SWD in liquid traps is tricky; the flies are teeny and only males’ wings have markings, which are hard to see, too. It’s difficult to tell which insects end up in the mix. Rothwell and Powers have evaluated insecticides to combat SWD. These products do help control the flies, but with SWD’s generation rate, populations become harder to control. Additionally, once the files are in the fruit, many insecticides are ineffective.

Unpruned treatment (left) and pruned treatment (right) in early spring, 2018. (Photos: MSU Extension)

Slowing SWD Culturally

Now the team is looking to pruning and mowing practices for effective SWD management.

Previous research showed SWD is driven by temperature and relative humidity, preferring wet, humid weather to hot and dry. SWD activity decreases at temperatures above about 86°F, and egg laying ceases at 91°F. SWD also doesn’t do well below 20% relative humidity.

Tart cherries have big canopies, which create a cool space and lock in moisture — perfect for SWD’s preferences.

“While SWD may move from blueberry and other crops with smaller canopies when it gets really hot during the day, I think they’re really happy staying in our tart cherry canopies the whole time,” Rothwell says.

Tart cherry growers mow at least two times per season: once around Memorial Day and once about a week before harvest in July. They traditionally prune established trees every two to three years, removing four to six larger limbs and cleaning up brush inside of the canopy. In 2017, Rothwell and Powers experimented with pruning and mowing orchards at different rates. They saw the most success with mowing every two weeks and pruning annually to help reduce SWD larvae in the canopy.

“We’ve seen some real benefits from increased pruning and mowing,” Rothwell says. “Our research results show that opening up the canopy helped reduce the level of infestation in tart cherries by 40%, with no insecticides at all.”

While growers tend to apply insecticides every seven to 10 days in the three to four weeks prior to harvest in order to manage SWD, the trials were conducted without insecticides.

Increasing the number of times a grower mows to an every-two-week program obviously means additional time, but traditional pruning and mowing rates may cost less than additional insecticide applications. These strategies may influence grower returns, particularly at a time when tart cherry market prices are historically low. Pruning too much also can reduce yields over time, so Rothwell and Power are continuing to research the issue, trying to find the best balance.

“We’re looking for the most sustainable way to control SWD,” Rothwell says.

Further replicating trials with higher SWD populations, such as they experienced in 2017, may determine if mowing every two weeks, annual pruning, or both practices will impact SWD infestation.

Understanding Flies’ Behavior

Rothwell’s team is also looking into exactly when the females start attacking the fruit. While 2018 started off with low infestations, in July the population increased six to seven times in just two days.

“Something happens in that fruit,” Rothwell says. “Something makes the fruit more susceptible — color, firmness, or something with the physiology of the fruit. We’re looking into that now so we can better convey risk level to growers.”

Rothwell says her team’s work is applicable outside Michigan and in other small fruit crops. SWD infestation is simply temperature and humidity dependent. Growers need to be diligent about managing SWD as rain, humidity, and wet weather will likely stimulate SWD activity. The flies seem to “wait” for moisture, and even with a small amount can become significantly more active.

“Whether it’s a block of raspberries or strawberries, it’s about how we can figure out the impacts of our system on the insects,” Rothwell says. “We know more than we did two years ago; back then we felt like we were in trouble. We’re just trying to put it all together, and we’re getting there.”