San Jose Scale Is An Old Pest That Is A New Threat To Apple Growers

Apple growers worldwide must deal with numerous insect pests in their seasonal management programs, including a large number of key pests that attack the fruit directly and render it unmarketable.

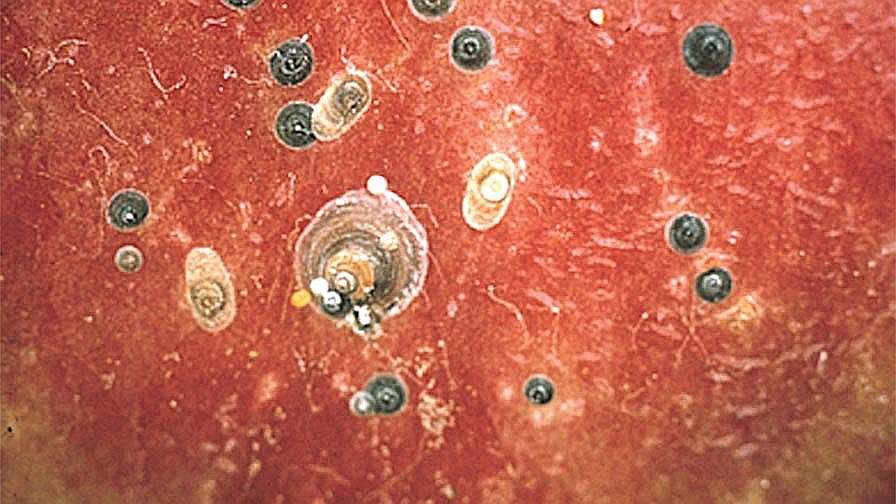

A reddish “halo” surrounds the point of scale attachment on the fruit, under the skin. (Photo credit: Art Agnello)

Dozens more species, often labeled as secondary pests, attack other parts of the tree, or else do less ruinous superficial damage to the fruit, and are therefore often considered less of a threat to overall crop health. Armored scales such as San Jose scale (SJS) fall into this second group, so the temptation over the years has been to minimize their potential to be a serious concern in most orchards.

However, relationships between pests and the crops they attack are rarely stable, and SJS is a good example of how they can emerge again as a significant challenge to healthy apple trees and fruit. Growers have seen a marked increase in infestations of what used to be considered a marginal insect pest over the last 10 to 15 years, largely because of changes in chemical control programs.

Asian Invader

Originally from China, San Jose scale, Quadraspidiotus perniciosus, was introduced into the U.S. (California) on infested plant stock in the 1870s. It is now cosmopolitan in its distribution, occurring nearly everywhere tree fruits are grown; it attacks principally pome fruits such as apple and pear, stone fruits — nectarine, peach, plum, and cherry — and such tree nuts as almond and walnut.

Frequent sources of infestation are nursery plants, or as wind-dispersed crawlers from both fruit and non-fruit hosts. Three principal factors favoring infestation by this pest are: the high number of potential host plants (700-plus species), a high reproduction rate, and an absence of effective natural controls in pesticide-based agroecosystems.

SJS mainly colonizes wood tissue of branches and twigs, although it establishes on fruit surfaces when populations are high. Damage is caused by feeding of the immature forms, “crawlers,” which suck plant sap, weaken the plant, reduce fruit and shoot growth, and desiccate foliage.

Infested trees usually exhibit less foliage and smaller fruits; a reddish “halo” surrounds the point of scale attachment on the fruit, under the skin, which is caused by the plant’s reaction to toxin in the saliva. Smooth-skinned fruits, such as apples and pears, are more susceptible than those with rough or velvety texture, like peaches.

There are two generations per growing season in the Northeast. They overwinter as immatures under scale covers called “black caps,” mature to adults in spring, and males emerge and mate around petal fall. Crawlers emerge about mid-June and in early August, an event that can be timed by using degree day (DD) accumulations — first generation: 310 DD (base 50°F) after first adult catch, second generation: 400 DD after first adult catch. It’s possible to monitor for crawlers using tape traps on scaffold branches.

National Menace

In 1914, the entire U.S. apple industry was threatened with extinction because of SJS resistance to lime sulfur — one of the first such documented cases in the U.S. The introduction of the heavy metal products like lead arsenate preserved the industry, but set the scene for repeated episodes of successes and failures using different insecticides.

Over the past century, New York recommendations for SJS control have evolved from just a side note related to prebloom oil use, to being listed (1967) together with pests typically present at the half-inch green stage, although with no direct advice provided for specific options, to being addressed (1982) in its own designated section during the summer, to the beginning (1987) of SJS-specific control options in both prebloom and summer programs.

The Food Quality Protection Act (1996) resulted in the cancellation or restriction of broad-spectrum insecticides such as methyl parathion and chlorpyrifos, which had formerly kept SJS occurrence to a minimum. Since 2010, we have added SJS management to New York stone fruit and pear recommendations, as these crops now suffer routine infestations.

Where does this leave us in dealing with this historic pest? Our programs now rely on insect growth regulators and — once again — prebloom oil sprays. Chronic infestations need to be addressed with well-timed summer insecticide sprays at first and peak (7-10 days later) crawler activity.

Also, attention must be paid to cultural measures, such as obtaining clean plant stock from the nursery. Problem populations are more common in larger trees with inadequate spray coverage, so early season pruning is advised to remove infested branches and open up canopy. Finally, use insecticides with different modes of action to avoid development of resistance.