The Future of Fruit Production Looks Bright North of the Border

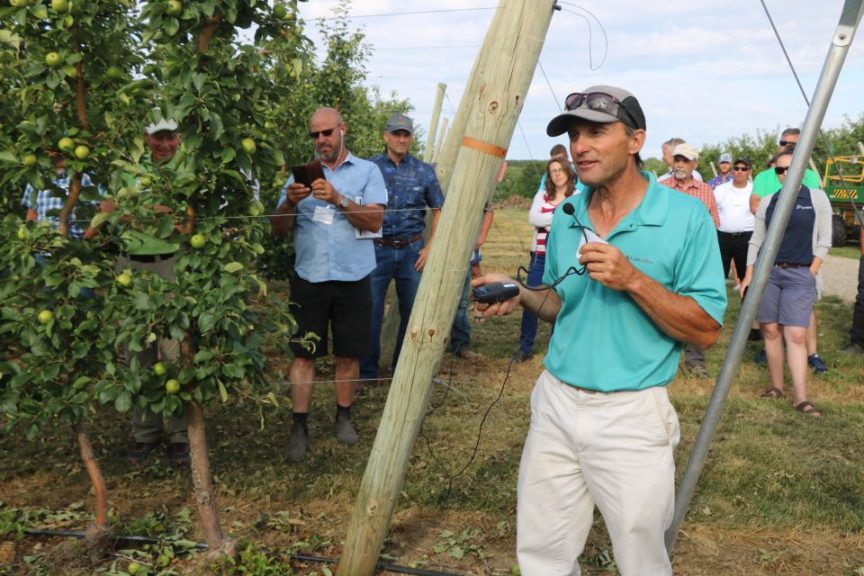

Day 2 of the International Fruit Tree Association’s (IFTA) Ontario Summer Tour in Canada was about the future of local fruit production. And, nowhere was that as evident as at Sandy Creek Orchards, an ambitious planting backed by Italian Investors.

“It looks like it’s been transplanted from South Tyrol,” remarked IFTA board member Tim Welsh.

The site of Sandy Creek was in orchard in the 1960s up until the early 2010s when it was converted to a cash crop. A real estate investment company looked to expand its portfolio of holdings and an orchard in Ontario looked like a profitable investment. When Italian investors were looking for a good site for a state-of-the-art apple orchard, Ian Furlong, a row-crop grower who manages agriculture investments, knew the perfect site.

“I always knew this farm would be a better value as another crop,” Furlong, who serves as the operations manager, says.

Last year, 15 acres of ‘Honeycrisp’ on M.9 were planted 26 inches apart in 10-foot rows. This year, 20 acres of ‘Honeycrisp’ were planted on M.9 and B.9, with an ultimate goal of planting 350 acres on the farm.

Since Italian investors are treating this Canadian farm like it’s a Western South Tyrol orchard, everything was shipped in from a company called FruitTop – cement poles, shade cloth, etc. It was a one-stop solution, Furlong noted, except for trees — which they were hoping to import but had to get from Canada — saying the Italian investor “wasn’t interested in sourcing from North America.”

“Every last bolt, nut, and zip tie,” Furlong said. “It’s not cheap to float cement posts on a boat,” Furlong says, saying it likely cost 30% to 40% more to import all the materials. And likely cost upwards of $30,000 Canadian dollarsper acre, without the land or tree costs.

Furlong says after visiting the South Tyrol region of Italy, he saw orchards on their third or fourth replant using 60-year-old cement posts.

“It was a no-brainer to justify the added expense. You have to milk that tree for 20 years to make up that expense.”

Water and frost protection are a large part of the orchard system, where overhead cooling and a drip line are utilized. The FruitTop package also includes black hail netting, which is pre-engineered for a static load. When the hail netting is weighed down with a certain load, a clip releases and the hail falls through. Furlong says this should help prevent any issues with destruction.

Black hail netting can reduce red coloring by about 25% has a longer lifespan, which is why it was selected.

Furlong was relieved the plantings are expanding gradually with 15 acres coming online last year and another 35 acres with 60,000 trees this year.

“My 15-acre experience of trees last year was a learning experience,” he says.

The Italian investors have brought along an Italian orchard manager named Stefano Paoli to oversee the technical elements of the orchard. While he’s never grown in North America, he has significant experience in orchards in South Tyrol.

“He has an aggressive approach to trees,” Furlong says of Paoli. “He wants to set maximum growth this year and crop next year.”

While that sounds overly ambitious, Furlong says he’s unsure if it will take five or 10 years to meet that goal.

“This is coming from a European management system,” he says. “When I say we need to take it slow, I mean we need to see what can be done here.”

For their next planting, Furlong says Paoli hopes to plant 2,700 trees per acre in a pedestrian orchard where trees would be about 7 feet tall.

“I’d rather start them at the top and slow them down than to start slow and see what they can do,” Furlong says.

Whaddaya Call ’Em?

There was discussion of what to call twin-stem trees at To No End Orchard. Multileader? Twin-stem? Two-leader? Twin-leader? Double leader? Regardless of what you call them, multileader trees might be new in North America, orchard manager Ken Denbok, whose family were immigrants from the Netherlands says “You think this is new? I saw this in the ’80s,” Denbok quipped.

Denbok estimates it cost him around $50,000 per acre in 2007 to plant his super spindle planting, which got him thinking about mutlileaders.

“If I can get a tree for $10, now I can get two trees for $10,” he says.

Multileader requires more planning and thinking, especially in the first two years, he says.

He planted ‘Gala’ on M.9 with 30 inches between each leaders and rows about 12 feet apart in 2015 and opted for M.26 when he planted another ‘Gala’ multileader block in 2018. Why M.26 for multileader trees?

“M.9 is a weak tree for me,” he says. “I don’t believe I get full production until year six.”

In order to get branching, he cut leaders and girdle wherever necessary. He also de-fruits weak leaders to boost growth.

Dembok says his productivity has been cut by a year in order to get trees to fill the canopy. But, he sees that he has more stems per acre, which should be a good return on investment. This started a lively discussion of whether cutting tree and orchard costs with multileader production makes sense economically.

Dale Goldy of Gold Crown Nursery says, “I’ve spent quite a few years arguing the value of second-leaf production. We have to start to look at the carrying costs of blocks each year that we don’t get production. That time to get to production is starting to be significant.”

Goldy noted that year in lost production of getting the multileader trees established is greater than it would be if single leader or more established double leaders were planted and could start yielding sooner.

Potted Tree Trial

At Apple Springs Orchard, Shane and Kyle Ardiel are conducting a trial to see how ‘Royal Red Honeycrisp’ on G.41 potted trees perform in a V-trellis system verses dormant planted ‘B42 Honeycrisp’ on B.9 trees.

While the dormant trees were 4 to 6 feet tall, the potted plants were not.

“Some were a foot tall and some were 2 inches,” Kyle Ardiel says.

While potted trees were cheaper, they were not as easy to plant as advertised.

“They were a nightmare to plant,” Kyle Ardiel says and his father, Shane, agrees.

“An hour after we started planting, I was ready to burn them,” Shane Ardiel says. “We were told that it was an easy plant.”

Kyle said they were tough to get out of the pot and they would lose dirt and probably some of the finer roots, too. The Ardiels also rented a U-Haul so that they would not get wind damage in shipping.

Kyle noted that the potted plants, “got shocked” when planted. And there was discussion about how tomato plantings from a greenhouse need some time to acclimate being outdoors before planting, so moving forward that would probably be a good bet.

The Ardiels decided to plant V trellis because Kyle thought going closer together and adding the V for light interception would help boost the number of apples on the tree.

Trees are one foot apart, and rows are 11 feet wide. Trees are tipped to 10 degrees.

“[In talks,] I heard 10 to 15 degrees and I heard if they get a crop on them, they could bend to 12,” Kyle Ardiel says.

The Ardiels are aiming for 80s or 88s, with about 50 apples on the tree and the ultimate goal of 80 bins per acre.

“We’re hoping we can still get decent color and not get too bushy,” Kyle Ardiel says about the V system.

Thinning Model 2.0

Tom and his brother Joe Ferri of T&K Ferri Orchards have implemented a retooled version of Phil Schwallier’s Michigan State precision apple thinning model.

“He revamped Phil’s spreadsheet to make it easier for a dumb farmer like me,” Tom quipped.

However, implementing this spreadsheet has been a lesson in patience, trust, and understanding of how the model works in the Georgian Bay region of Ontario. With experience, there’s a bit of variation on degree days, and Tom Ferri says he starts measuring at about 75-degree days.

The first year Joe and Tom used the model was in 2014. But, “it took him a while to accept this,” Joe Ferri says of using the spreadsheet.

In 2014, Tom put two sprays on back-to-back without consulting with Joe and the spreadsheet. The results were effective.

“That’s the first year we didn’t have to thin anything,” Tom Ferri quipped.

Tom says he’s happy with using Joe’s version of the thinning model, noting ““this model is time-consuming, but it works”

He favors growing in a super spindle system due to the ease of the training. He planted his first ‘Honeycrisp’ on the super spindle system in 2008.

“My dad told me ‘if you don’t do this, quit,’” he says.

His trees are all 18 inches apart, with 10-foot rows.

“It’s very simple to teach people, let’s get five (clusters) in each section,” he says. “We just want a narrow, narrow canopy; we want light, and we want color — high, high color.”

And, the growth style of ‘Ambrosia’ makes it a perfect fit for super spindle, noting “you better plant this close with this apple.”