A Better Way To Gauge Chilling Hours

With 2014 wrapped up, it’s a good time to take stock of the impacts of the warm winter of 2013-14.

Last winter was a clear demonstration that simply counting chill hours is not a great way to approximate how California fruit and nut trees are affected by chill. A newer way of counting, the chill portions model, can help growers better track chill and anticipate low chill years.

Chill accumulation last winter fell behind in January and never caught up. Many orchards showed classic symptoms of low chill and suffered decreased yields as a result. According to the chill hours model, last winter was actually an average chill winter. The trees obviously did not get the message. The chill portions model, on the other hand, showed chill down 25% across the Central Valley.

Was last winter just a blip on the radar? Is it worth making changes to be ready for more warm winters? Records since the 1950s show we get low chill every 10-20 years. It’s likely these cycles will continue, but the severity of these occasional low chill winter will likely increase over time as temperatures rise.

Starting Out

The first step to preparing for more warm winters is counting chill better – moving from chill hours to using the chill portions model. Starting the switch now will mean being more comfortable with the new model when another warm winter strikes. What makes the chill portions model (also called the Dynamic Model) better? There are three basic differences between the models.

1) The chill hours model counts any hour between 32°-45° F as the same. Chill portions gives different chill values to different temperatures. No more wondering about the value of ‘warm’ chill hours. Temperatures between 43°-47° F have the most chill value. The chill value on either side of that range are lower, dropping to no value at 32° F and 54° F.

2) The chill hours model only counts up to 45° F. Chill portions count up to 54° F. This makes chill portions better able to approximate how the trees we grow, most of which evolved in fairly mild climates, count chill.

3) The chill hours model does not subtract for warm hours. Chill portions can. The math is tricky, but the concept is simple: Chill portion accumulation is a two-step process. First, a ‘chill intermediate’ is accumulated, but can be subtracted from if cold hours are followed by warm hours. Second, once the chill intermediate accumulates to the certain threshold, it is converted into a ‘chill portion’ and the chill intermediate count starts over from zero. The chill portion cannot be undone by later warm temperatures.

Hokey, But True

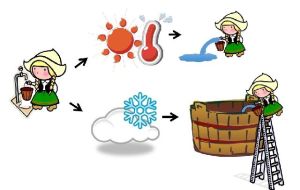

It’s hokey, but I think of it as filling ‘chill buckets’ that then fill a ‘chill tank’ like the girl in the graphic. Cold hours add to what’s in the bucket until it’s full. Warm hours along the way can spill out some of what’s in the bucket. But once the bucket is full and dumped into the tank, that chill can’t be spilled or lost.

It’s hokey, but I think of it as filling ‘chill buckets’ that then fill a ‘chill tank’ like the girl in the graphic. Cold hours add to what’s in the bucket until it’s full. Warm hours along the way can spill out some of what’s in the bucket. But once the bucket is full and dumped into the tank, that chill can’t be spilled or lost.

Last January shows the need for this component. Warm January day temperatures subtracted from the cool temperatures of the night before, but did not subtract from cool temperatures in November and December.

There’s two ways you can track chill portion accumulation – let the University of California do it for you with California Irrigation Management System (CIMIS) data, or use your own weather system.

To use the UC resource, go to the Fruit & Nut Research & Information Center’s Cumulative Chill Portions calculator. Click your nearest CIMIS station, put in the start date of Nov. 1 and click “View Data.” The site gives a graph and table of the chill accumulation this winter and the previous five.

To use your own weather system, you need a file with hourly temperature data. Then visit Kitren Glozer’s chill model website, download the “Dynamic Model” Excel file and the step-by-step “Dynamic Model & Chill Accumulation Guide” pdf, and follow the instructions.

For more details on the chill portions model, including the chilling requirements of different crops in chill portions, check out thealmonddoctor.com/author/kspope. ●

Pope is a University of California Cooperative Extension farm advisor for almonds, prunes, walnuts, and other orchard crops in Sacramento, Solano, and Yolo counties.