What Nut Growers Should Know About the Carpophilus Beetle

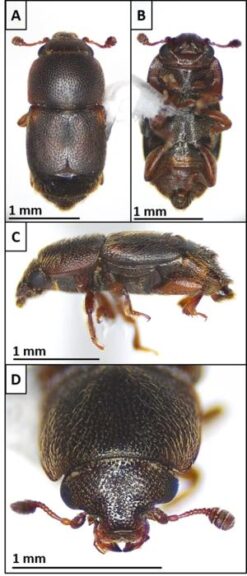

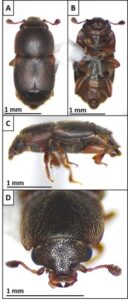

Another invasive insect to wreak havoc on crops? Meet the Carpophilus beetle. Photo by Jhalendra Rijal, University of California Cooperative Extension

The hits just keep on coming. From the landing of the Asian citrus psyllid a quarter century ago — which later spread the deadly citrus disease Huanglongbing (HLB) throughout Florida on hurricane-fueled winds — to the newest pest spreading nationwide, the spotted lanternfly, it seems nonstop. But when you consider how many insects are spreading because of the technical and economic shrinking of the globe, we should be used to them by now.

The Entomological Society of America estimates the U.S. is adding about 11 new exotic species each year, with about seven of those being important pests. Overall, it estimates that invasive species — including both insects and weeds — cost the U.S. more than $122 billion per year. California growers, farming such an extraordinarily wide range of fruits and vegetables, can be particularly vulnerable. According to the Society, invasive species are responsible for up to 50% of the crop losses in California, a state that produces half the nation’s fruit and nut crops.

The latest pest to hit the Golden State is Carpophilus truncatus, more commonly known as the Carpophilus beetle. It doesn’t appear to be a threat in most of the rest of the country because only nuts have been attacked, so far. To date, almond and pistachio orchards infested by Carpophilus beetle have been confirmed in numerous San Joaquin Valley locations, suggesting that the establishment of this new pest is already widespread, according to Jhalendra Rijal, University of California Cooperative Extension IPM Advisor. In fact, some specimens from Merced County were from collections made in 2022 suggesting the pest has been present in the San Joaquin Valley for at least a year already.

“It has likely been here for a few years based on the damage we’ve seen,” Rijal says.

COMMON DOWN UNDER

Carpophilus beetle has been infesting almond orchards in Australia since 2013 but was not known to be present in California. Rijal himself has found the only California walnut infestation to date, but it has also been found in Italian walnuts, as well as Australia, where it’s also been found in pistachios.

Rijal says damage from the beetle can be confused with many California growers’ top pest, navel orangeworm (NOW), which, like Carpophilus beetles, feeds directly on the developing kernal. Adults chew through the shell, leaving a small, 2 to 3 mm, circular hole, and lay eggs on the kernel. Carpophilus are quite small, with adults measuring about one-tenth of an inch.

In Australia, it frequently is found with carob moth, which Rijal describes as “their navel orangeworm.” Interestingly, carob moth is found in California, but is not known to be a problem in nut crops. Both beetles are two major pests that almond growers have now been managing since their first introduction about a decade ago.

In almonds, the beetles seem to attack mostly ‘Nonpareil’ nuts, likely favoring the variety for the same reason NOW does. Its shell is thinner, and hull split, which is when the beetle lays its eggs, occurs earlier than in other varieties. But multiple infestations have been found in other varieties, including ‘Monterey’, ‘Fritz’, ‘Sonora’, and ‘Independence’.

While information from Australia has been incredibly helpful, more studies on this pest in California are needed. For example, there is currently no insecticide recommended for the pest, and those recommended for NOW don’t work on Carpophilus, based on Australian experience. To address this and other issues, Rijal is collaborating with colleagues Houston Wilson, Associate Cooperative Extension Specialist, Dept. Entomology, UC Riverside, and David Haviland, Entomology Farm Advisor, Kern Co., to develop a series of studies on the ecology, monitoring, and management of this new pest in 2024.

“While we’ll be looking into insecticides in the coming seasons,” he says, “there’s a lot more research ahead on other aspects of this pest, such as their ecology and phenology, as well as improved monitoring strategies.”

KEEP IT CLEAN

The ability to use insecticides to control Carpophilus beetle remains unclear. One obvious problem with them is that the majority of the beetle’s life cycle is spent protected inside the nut, with relatively short windows of opportunity available to attack the adults while they are exposed. The location of the beetles within the nut throughout most of their life cycle also allows them to avoid meaningful levels of biological control.

In the absence of clear chemical or biological control strategies, the most important tool for managing this beetle is crop sanitation, since these beetles overwinter in the remnant “mummy” nuts. Winter sanitation is already strongly recommended to deal with NOW, since they, too, overwinter in remnant nuts, but it may be even more critical for Carpophilus, given the lack of other control options.

As with NOW, growers need to ensure that mummy nuts are removed from trees, blown to orchard middles, and destroyed by flail mowing before next season. It is also important to bear in mind that overwintering pest survival is better in nuts, both in trees and on the ground during drought conditions for NOW, but for beetles, wet conditions seem to favor their population. In winters with minimal rainfall, typical sanitation practices should be enhanced accordingly.

Rijal notes another difference from NOW, in that Carpophilus prefers to overwinter in ground mummies, and with NOW, growers are more concerned with tree mummies.

“Make sure you shred those nuts on the ground by mid-March or so,” he says. “The beetles are very tiny, and it might be important to do a double-pass to shred the mummies. Shredding is even more important because the Carpophilus are so much smaller than NOW. NOW are easy to kill. With Carpophilus, if you don’t shred well, you might not kill them.”

Photo by Jhalendra Rijal, University of California Cooperative Extension;

SAMPLING IS CRITICAL

Damage from Carpophilus beetles is so new to U.S. growers that entomologists are busy playing catch-up, analyzing the data to come up with strategies for growers to deal with the pest, which is so different from pests encountered in the past. For information, Americans are looking Down Under, as the Australian almond industry has dealt with Carpophilus for more than a decade. Following is a condensed version of a guide to sampling for Carpophilus prepared by Agriculture Victoria Research of Australia.

Samples of new nuts collected shortly before harvest provide useful information on the distribution of Carpophilus damage across orchards. This can help growers plan the most appropriate harvest and postharvest management of the crop, such as earlier harvest and prompt fumigation and/or processing to limit further damage in crops from more heavily infested blocks.

Sampling position is important. Nuts collected from the ground immediately after trees are shaken represent the entire crop throughout each tree, and so provide a good overall average of damage or infestation levels of any pest throughout the tree. Nuts collected from trees before harvest represent only those areas from which they are collected. Unless the samples include nuts from all areas of the trees, especially different heights in the canopy, the average damage level found in the samples may not reflect the true damage level of the crop.

To determine Carpophilus beetle damage levels in new crops, sample nuts from the ground after tree-shake, or ensure the full height of the canopy is represented in samples collected directly from trees.

Timing of sampling is vital. Carpophilus beetle infests almonds as soon as hull split occurs, and kernel damage increases rapidly until the nuts are harvested and disinfested or processed. Because of this rapid growth in damage, preharvest samples collected a considerable time (e.g. 2-3 weeks) before harvest may lead to a significant under-estimation of actual crop damage levels at harvest. Growth in infestation and kernel damage in new nuts by Carpophilus beetle over time.

Preharvest samples to determine damage levels from Carpophilus beetle should be collected as close as practicable to the time of harvest.

Nuts’ location in winter sampling is crucial. Sampling of old mummy nuts and leftover crop from the most recent harvest can be used to determine the levels of Carpophilus beetle infestation being carried into winter. This may help orchard managers target hygiene efforts toward the most heavily infested blocks. Sampling position is important. Extensive sampling of mummy nuts from high and low in tree canopies and from the ground, over two winters, found that a much greater proportion of nuts on the ground is infested with live Carpophilus beetle, compared to nuts from low or high in the tree canopy.

When sampling mummy nuts for Carpophilus beetle infestation in winter, collect nuts from the ground under trees rather than from the trees themselves.