Almond Growers Fine-Tuning Irrigation

For decades, almond growers have gotten steadily better at becoming stewards of that most precious resource — water — but you certainly wouldn’t have known it sampling consumer news media during the California drought that ended (temporarily) with the wet winter of 2016-17.

Back then, all the talk was about how it takes a gallon of water to produce a single almond, never mind that other foods — meat is off the charts, for instance — take a lot more water to produce. But growers since have been working extra-hard through efforts spearheaded by the Almond Board of California, among others, to not only conserve water, but communicate those conservation endeavors to the public.

Now almond growers have technology available from an Oakland, CA, company called Ceres Imaging that recently received a ringing endorsement from University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE) Farm Advisor Blake Sanden. The UCCE Irrigation and Soils Farm Advisor in Kern County, along with several colleagues in the state, has had a study underway since 2013, the results of which will soon be published.

Blake Sanden

Maintaining ideal irrigation levels is a huge challenge for growers, as is predicting the final harvest tonnage, which is why the study examined the usefulness of Ceres aerial imagery in those areas. Detecting deficient irrigation quickly is one way Ceres images offer early warnings to growers.

“Findings over the last four years show that the average Ceres conductance measurement from its imagery over the season has provided the best correlation with applied water,” says Sanden. “While there’s no perfect predictor of final yield, Ceres aerial sensing of canopy plant stress has a significant relationship with final yield.”

Historical Perspective

Sanden has a unique perspective on almond growers’ water usage. From 1988 until 1992, when he joined UCCE, Sanden worked for Paramount Farming (now Wonderful Orchards) of Bakersfield, where he was introduced to almond growing. He soon learned that the UCCE recommendations for the amount of water the trees needed was too low to get huge yields.

The first almond crop-water use number that was put out by the University of California (UC) in the mid-1960s said top end crop coefficient would max out at 0.9. That was equal to 42 inches in the San Joaquin Valley and 39 inches in the Sacramento Valley, where precipitation is generally greater.

The UC also provided a recommendation on when to start the annual irrigation. At that time it was not until April, with subsequent shut-off in mid-October. Those original numbers were generated using neutron probes under flood-irrigated almonds grown near UC-Davis, says Sanden, with the frequency of flooding anywhere between 11 and 20 days.

Back then, flood irrigation was the norm. In fact, growers have made remarkable strides through the years in adopting technology, even though some of that technology seems rather basic today. From 1991 to 2010, California almond growers increased the use of sprinklers and drip irrigation systems instead of the traditional method of using gravity to flood fields, from 33% to 57% of total acreage.

“In those years (the 1960s), 1,300 pounds to the acre was average, and that was the average yield all the way through the ’80s,” he says. “It really was not until mid to late ’90s that you started having a group of serious, more educated agronomists and growers pushing for greater production.”

Sanden already had an inkling the recommendation might be too low. In the orchards he was charged with irrigating, by mid-May all the hand and neutron probes showed he was losing water storage below three 3 feet. The level only went down at most two 2 feet.

Sanden already had an inkling the recommendation might be too low. In the orchards he was charged with irrigating, by mid-May all the hand and neutron probes showed he was losing water storage below three 3 feet. The level only went down at most two 2 feet.

“Following that UC schedule, I was losing storage,” he recalls thinking. “What’s going on? These trees are pulling more water than the UC says they will.” Part of the problem was the mindset back then about irrigation.

When Cotton Was King

“Those were the days when cotton was still king in the (San Joaquin) Valley. We started seeing dwindling acreage by the late ’80s, but cotton was still the main crop. The equipment boys ruled the roost. ‘Keep your water out of the way of our equipment, you’ve got to turn the water off,’” they’d say. “‘Are the trees going to stress? I don’t care, I have equipment to run.’”

Another factor was that many believed at the time that almond trees naturally shed their leaves at harvest. But that wasn’t the problem, Sanden knew. The trees were shedding leaves because they needed more water.

Not too long after that, the UCCE’s David Goldhamer came out with studies showing a lack of water was the greatest cause of reduced yields. But until then, yields remained low, at about 1,300 pounds.

“If you got a 2,000-pound yield you thought you’d died and gone to heaven,” Sanden says, noting that average yields now differ by region, but they vary across the state from 2,300 to 2,600 pounds. “Today, if you had 2,000 pounds, people would ask ‘What went wrong?’”

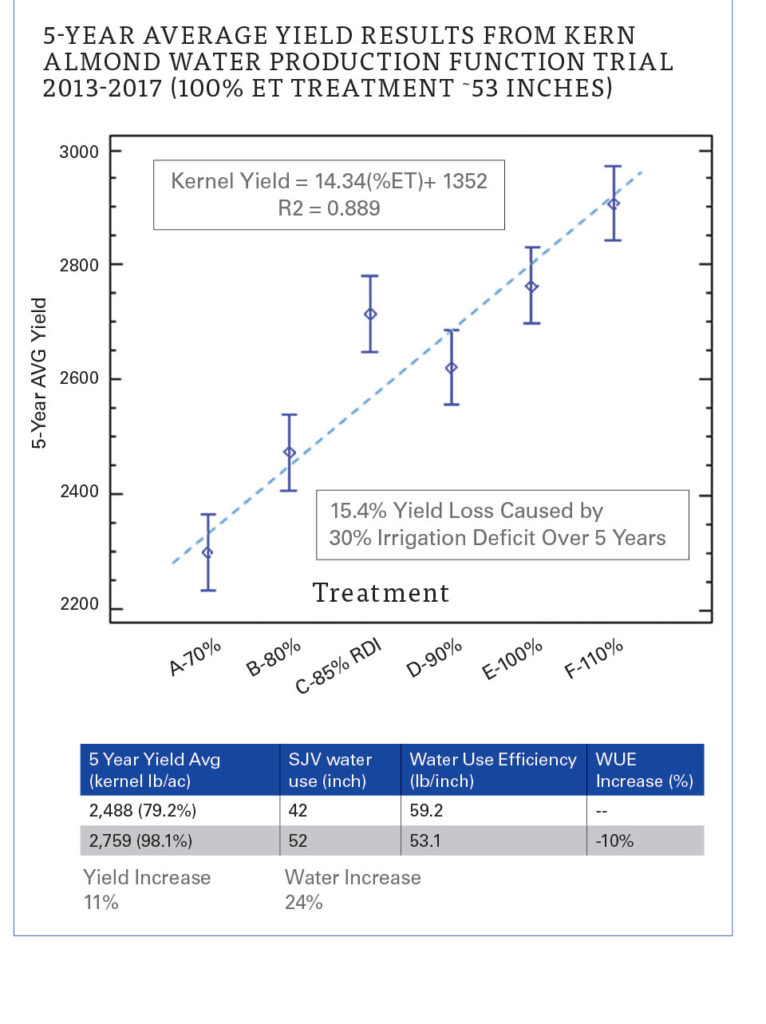

That’s of course chiefly because today’s growers are so much more water-wise. Sanden says almond trees can use 52 inches in the San Joaquin Valley, giving a 79% kernel yield increase over the 1986-1990 yields, with only a 24% water increase. This is actually a 45% increase in Water Use Efficiency (WUE), in terms of pounds of almonds per inch of water. But there are other reasons for the increased yields, such as better varieties and rootstocks, improved fertility, and more intensive canopy/disease/insect management.

“The Olympia Beer guys had it right, it’s the water and a lot more,” he chuckles.

Sanden adds that the UC recommendation, which comes out to 42 inches in the San Joaquin Valley, still has merit. There is a yield loss compared to 52 inches, but it’s only 11% if your other factors — varieties, fertility, disease/insect control — are optimal.

Sanden adds that the UC recommendation, which comes out to 42 inches in the San Joaquin Valley, still has merit. There is a yield loss compared to 52 inches, but it’s only 11% if your other factors — varieties, fertility, disease/insect control — are optimal.

In addition, the crop per drop WUE for the current management practices is now actually greater for the reduced irrigation (42 inches) amount.

“Maximum yield is still at maximum water use,” he says, “but this is not necessarily maximum water use efficiency.”

In-Flight Water Gauge

Efficiency is what Ceres Imaging can provide, says Sanden, citing the five-year UCCE study, which had funding support from the USDA. Aerial images of orchards can effectively tell farmers which almond trees aren’t getting enough water.

Researchers from the UCCE are confirming the utility of Ceres Imaging’s new-to-the-industry aerial views of farmland that helped the startup win a water innovation competition last year. The preliminary results follow four years of replicated research plots in a large commercial almond orchard.

Ironically, California growers’ increased use of sprinklers and micro-irrigation systems can be blamed for part of the problem. That’s because micro-irrigation, the method that ordinarily offers the highest water use efficiency — the most crop per drop — is prone to clogging and other maintenance problems, which can stress crops and reduce yield.

“Water is the number one input for most growers and is managed carefully in terms of how much is used and when,” says Ashwin Madgavkar, the CEO and founder of Ceres Imaging. “This study shows that Ceres imagery can be used with high confidence to monitor if your crop is getting sufficient water or if the crop is in a water-stressed condition, so you can make timely corrective actions. Ultimately, the tool can be used to help catch issues before they result in crop losses.”

Ashwin Madgavkar

Madgavkar says aerial imagery for agriculture is certainly not new. But Ceres not only looks at the variety of light wavelengths, it runs them through a series of algorithms that eliminates error coming from the soil background and can also indicate water status and nitrogen content.

“We have invented new imagery technology that allows us to see water and fertilizer issues, way more than the naked eye,” he says. “We help growers with over- or under-watering — valve issues, filter issues — all that can go wrong with modern irrigation systems.”

Madgavkar’s background seems appropriate, as he founded the company after getting his MBA from Stanford University, where he also studied Earth Sciences. He had previously worked on farms in South America, where he saw a real lack of data lead to waste. Back in California, he thought he could make a difference.

“After talking with lots of farmers — in 2013-/14 when the drought was really getting bad — we raised VC (venture capital) and used that to build the first prototype that could sense a plant’s real-time water content,” he says.

Just four years later, between 15% and 20% of the almond and pistachio acreage in California is surveyed by Ceres.

“We’ve been able to take our technology that measures real-time water status and work with growers on a commercial basis,” he says. “We could show it wasn’t snake oil.”

Madgavkar says they started with almonds and pistachios not only because of the drought, but because they are high-value, high-margin crops that were great for developing technology. Today, CERES (Ceres Imaging) has nearly 50 employees, not just in California, but in the Midwest to work on the big-acreage program crops like corn and soybeans.

“We want to be able to sell to growers of all crops,” he says. “All growers can use imagery to make them more efficient.”

Pay As You Go

They can charge per acre, or per image. Growers can sign up for weekly or monthly images. All are provided on a subscription basis, so the growers don’t have to pay anything in advance.

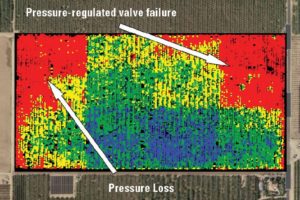

This image of an 80-acre almond orchard block in Kern County, California, clearly shows hot spots indicating irrigation problems that can be immediately corrected by the grower.

Another attraction is that no new equipment is needed. With a commercial field, they usually fly over with a basic small airplane to obtain images for analysis.

“We run proprietary analytics and software to find plants’ moisture levels,” Madgavkar says. “We look for, say a linear pattern — like a plugged drip line. By contrast, a rectangular pattern might indicate a valve problem. We can usually identify the root cause right away, which is valuable information because the grower can fix the leak — or change out the valve — right away.”

However, because it’s new technology and imagery — patent pending — they take time to explain to growers what will or will not work.

“We’ve looked at images covering millions of acres,” he says, “so we can help the farmer interpret data.”

Working with growers has actually been the easier part of the process of growing the company. They will start by showing growers something simple, like a valve or pump issue.

“That enables them to pick the low-hanging fruit in improving their infrastructure before they start losing production,” he says. “When you’re scouting on an ATV, it’s hard to see the forest for the trees. By the time you see stress with your naked eye, the tree has been undergoing stress for some time.”

Madgavkar says if you can make a solid business case for a technology, farmers will buy it. They are open-minded because they are looking for an edge. The tough part was educating potential investors about agriculture.

“There was a lot of headwind because Ag is just not part of VC world,” he says, before adding with a laugh: “Navigating selling investors and farmers at the same time was interesting.”

After starting by measuring water, then fertilizer, they are now moving into pest and disease modeling. In the future, they will do yield forecasting.

But for now, Madgavkar is happy to provide growers with some answers on saving water. However, he thinks saving on another scarce resource, labor, could perhaps have just as much impact in the very near future.

“It’s the next generation of scouting, well beyond just driving around in truck; you need fewer people to cover more ground,” he says. “Imagery will be a powerful tool that will just be part of farming.”