Finding Natural Solutions To Fight Walnut Pests

Daniel Unruh grew up farming with his father in South Dakota before coming to California to own part of his father-in-law’s 190-acre Princeton Ranch in 2013. Although the Colusa County grower has worked in swine, soy, and a variety of other areas, he now focuses on walnuts. His previous experience had revolved around conventional crop protection methods using synthetics, but today he’s attracting attention with his innovative inventions and regenerative farming techniques.

It all started with nematodes.

“We didn’t know we had a nematode problem until after we planted the walnuts and it was too late to fumigate,” he says.

Unruh found that using a “cocktail” of several kinds of grasses, legumes, and forbs resulted in the best soil health and dramatically reduced nematode numbers. After finding that shredding the cover crop led to excess biomass that created a seal over the top and rot at the bottom — along with a “tremendous stench” — Unruh modified his roller crimper with chevron crimps to put more weight and pressure on the ground over a shorter area than with a flat bar. Now he plants his cover crops before the rainy season in the fall. The following spring, he uses the roller crimper to roll down the cover crops and crimp the stems.

“The crimper keeps the plant material aerobic by covering the soil while keeping a dimly lit, moist, well-aerated environment, which is conducive to healthy soil biology,” he says.

MIGHTY MITES

That success led him to consider an unconventional approach for another issue: two-spotted spider mites. After working with a local insectary, he decided to try natural predators, californicus mites, and beneficial insect food. The insect food includes wintergreen oil, which releases a smell that attracts pest predators.

“It’s not the smell you and I would associate with wintergreen,” Unruh says. “There’s a chemical compound that is the same that healthy plants release when they’re being attacked by pests. It’s basically a signal to ‘Bring on the predators because I’ve got a problem!’”

After a small initial application, Unruh saw that natural californicus mites appeared. He ordered more mites and applied additional beneficial insect food systematically to areas of his orchard.

“I put the mites halfway in between the beneficial insect food so that, as they hit the trees and ground, they smell food,” he says. “Then they put their walking shoes on and start hiking toward it, eating the spider mites along the way and cleaning up my problem.”

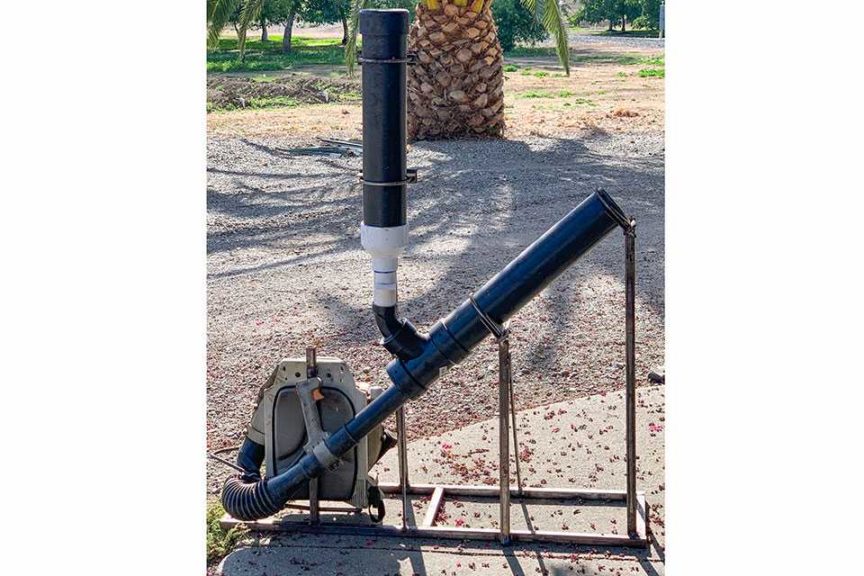

Of course, Unruh’s californicus mites application involved some tinkering too. He modified a leaf blower to blow the mites into the trees.

Several weeks later, his trap checker reported that the predators had “cleaned house” on the pests. A field worker said Unruh had “beneficial insects from corner to corner” on his ranch.

This approach has resulted in reduced expenses — mainly from avoiding synthetic nitrogen and using less fuel — and consistent success over the last three years. Unruh hasn’t done a nitrogen application in that time and suspects a correlation between over-applying nitrogen and the influx of harmful mites.

Unruh’s work isn’t done, though. He’s noticed that even though he is making more money per ton than his neighbors who use only conventional farming practices, his overall yield is declining, and he’s ending up with less gross profit. He suspects his soil’s natural nitrogen levels aren’t yet strong enough, and another synthetic application may be necessary.

Unruh isn’t opposed to doing what is necessary. He values his soil’s health and longevity and the resulting nutrient-rich food but understands he needs to do what’s best for his business.

“We in production agriculture often think the sure fix is to run chemistry because we don’t understand the whole problem,” he says. “Sometimes that’s true, but we have to be careful not to close our minds to other alternatives that may work as well for far less money and be better for the overall system instead of just nuking everything and having the problem possibly come back worse. Just because you’re a conventional farmer doesn’t mean you can’t use some organic or regenerative practices. If you can find a successful system that uses a bit of both practices and culminate the two, you may have a better result.”