Ways to Monitor Water Quantity and Quality for Almonds

The calls last spring, as almond growers were concerned about their crops in the Fresno, CA, area where Mae Culumber works as a University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor.

In a session at the annual Almond Conference in December, Culumber addressed a standing-room-only audience that packed a meeting room for a session titled “How Your Trees Work Under Adequate Water Supply and Deficit Water Supply.” Culumber addressed the situation in the Southern San Joaquin Valley; her colleague, Luke Milliron, UCCE Farm Advisor in Butte, Glenn, and Tehama counties, addressed the state’s Northern almond-farming region.

Culumber says that by early summer, the calls were becoming more frequent, and many of the growers were reporting similar problems, the true nature of which was revealed when the crops were harvested. That’s when they found that while in a normal year growers would average 26 almonds to the ounce, this year it was 28 to 30.

“A lot of growers were reporting smaller nuts, but I talked to people with enough water, and they had a similar outcome,”

she says.

Spring was unusually warm, and there’s no question heat-induced plant stress cuts the rate of photosynthesis and carbohydrate production, which will affect the crop, she says. But it was clear there was more to it than excessive heat or the drought.

“It was likely a combination of causes: heat, water stress, canopy shading, and humidity in the lower canopy,” she says.

UNIFORMITY DESIRED

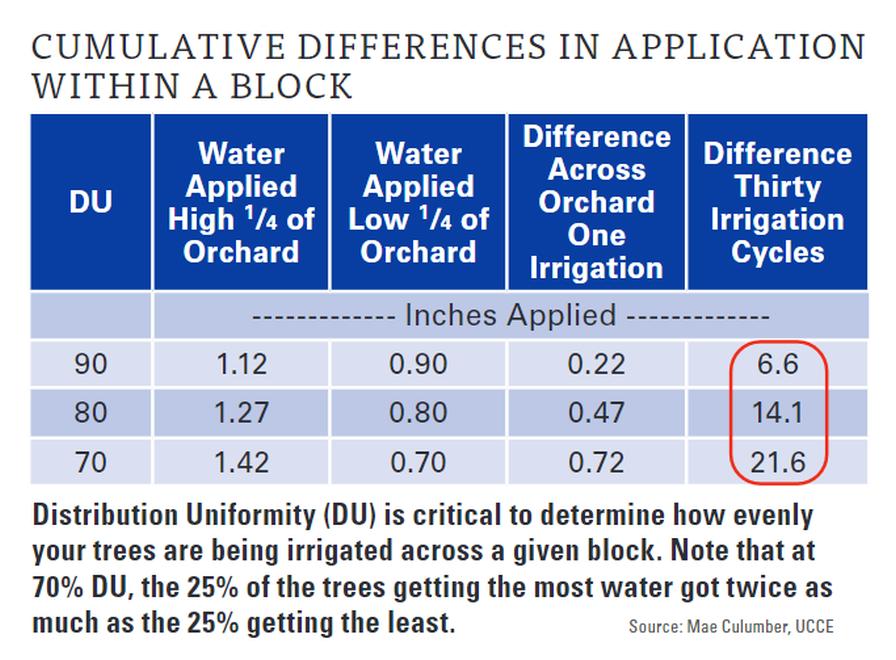

However, in analyzing growers’ irrigation systems, Culumber did indeed uncover problems. Many had lower than desirable uniformity, meaning some trees were getting far less water than others.

For example, Culumber notes that when an irrigation system’s distribution uniformity (DU) dropped to 70%, the ¼ of the trees in the block receiving the most water were actually getting more than double as much water as the ¼ of the trees getting the least amount. That difference, when played out over 30 irrigation cycles, would be more than 20 inches applied. Furthermore, the water quality left a lot to be desired.

“Drought can cause water quality problems, which can clog micro-emitters,” she says. “Irrigation system maintenance is critical.”

Surface water, which is not as available during a drought, is generally purer than the ground water many growers have had to rely on during the drought, which has more particulates and organic contaminants. And impurities can cause further problems.

“Lots of iron, for instance, will make organisms grow, or applying lots of gypsum can clog emitters with calcium,” Culumber says.

NORCAL PROBLEMS

Following Culumber, Milliron noted that while the northern parts of the state historically get more rainfall than those to the south, that doesn’t mean they haven’t encountered their own drought woes.

“We have our water problems too,” he says.

But echoing Culumber’s concerns about water quality, he quotes his colleague, UCCE Farm Advisor Franz Niederholzer, who manages the esteemed Nickels Soil Lab: “You may have water, but how clean is it?”

Particularly troubling, Milliron says, is that trees were showing high amounts of chloride. While fruit and nut trees need small amounts of chloride, when it is in excess, trees can suffer from salt toxicity.

However, Milliron says he was most concerned about the quantity of water trees were getting, more specifically, the fact that many growers can’t adequately determine how their trees are doing. That’s because just 30% of the state’s almond growers use pressure chambers, which can precisely measure a tree’s water status, showing problems before the tree itself shows any signs.

“I hope we can bring that (percentage) up across the industry,” he says.

Milliron notes there is now an available alternative to pressure chambers, automated water-potential devices. However, because you can pick only a single tree to attach the device, it gets pretty difficult to determine a perfectly average tree.

If nothing else, Milliron says growers should track rainfall and compare it with the average received every two weeks from October to January.

Growers should be asking: “What was the rainfall? Should I be replacing (any deficit) with irrigation?”

But if growers took away anything from Milliron’s presentation, it is that they should be using pressure chambers, especially when the state is on the verge of serious drought, depending on how the current rainy season plays out. Considering the stakes, there’s no good reason not to use a pressure chamber, he says.

“A pressure chamber will pay for itself if you farm as little as 80 acres,” Milliron concludes