2 Big Trends Impacting Vegetable Growers in Colorado Right Now

Each year, the editors of American Vegetable Grower make an effort to visit farms in an area we don’t normally see. This year, I flew to Colorado and spent a couple weeks touring farms, research fields, and gaining an understanding of how the area functions.

Here are just a couple of things I learned about Colorado.

Water Struggles

A common theme for any western U.S. tour will be water access. Rain patterns have shifted over the past 20 to 30 years. Some parts of the U.S. are getting more rain — like the Northeast and parts of the Midwest — while the entire West saw a decline.

Driving around the Rocky Ford growing area in the Arkansas Valley in southeast Colorado, I saw several large growing fields with no production. The city of Aurora, a Denver suburb that’s a two-and-a-half-hour drive away, purchased the fields almost 20 years ago to obtain water rights. It’s doing the same now in the larger growing area around Greeley, CO.

This tug of war between agriculture and those living in urban areas with few ties to farms has been a multi-year battle. And it’s one that is likely to continue.

The state’s vegetable growers are taking steps to bridge the gap between them and urban regulation makers.

Robert Sakata, President of Sakata Farms, became the first grower to serve on a state level water board. He now has a healthy list of credits to his name in this area, including serving on the Colorado Water Conservation Board, Water Quality Control Commission, and Colorado Water Congress.

Sakata also was the founding president of the Colorado Fruit & Vegetable Growers Association, a very young association when compared to other states. I met several growers who are currently on the association board.

Historically, many growers in Colorado had a philosophy of staying out of sight, protecting farms through secrecy. Today, many growers are actively involved in government in some form, giving a voice to agriculture.

Weather Issues

Due to its altitude, much of Colorado has cooler weather and shorter seasons. Even hot areas like Rocky Ford have overnight lows in the 50s, making it the site of the most dramatic single-day temperature shifts in the U.S.

Like much of the country, 2023 has been an unusually active weather year for Colorado.

In the northern and central counties, an unusually wet spring prevented heavy machinery from entering fields. That resulted in many late plantings, making growers nervous if harvest will beat first frost.

The fields growers managed to plant on time faced weeding issues, since cultivators couldn’t enter the wet fields during critical early periods.

Hail also is a perennial Colorado foe. The typical Colorado farm layout is to spread fields across several miles as insurance that hail in one area will spare fields in others.

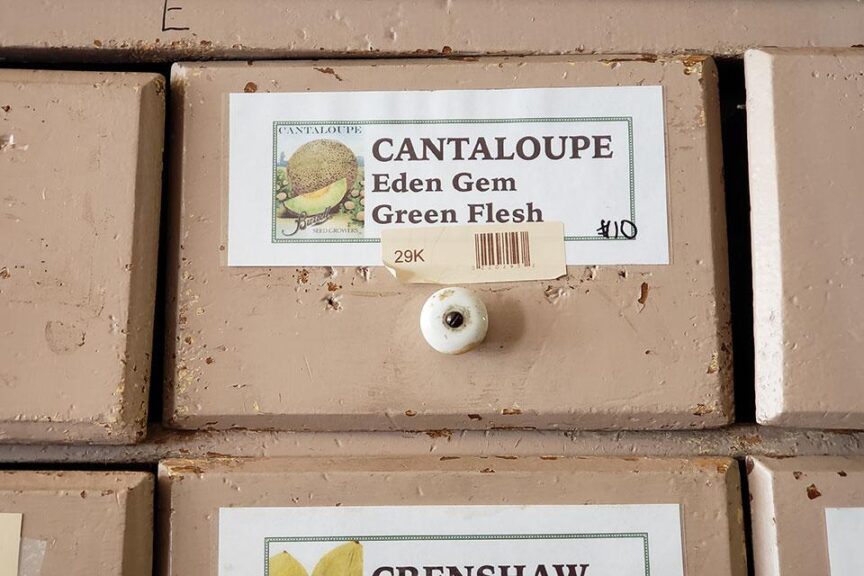

In the Arkansas Valley in southeast Colorado, hailstorms came through so often that contingency failed. Many farms had all their fields hailed out. The added heat this summer has helped push second plantings along, promising strong pepper and melon harvests.