5 Studies That Help Explain How Organic Production Works

Organic lettuce growing in Monterey County, California. Photo by Richard Smith.

Many people think the reason growers use organic production is due more to opinion than science, that it’s a growing method popular only because of consumer demand.

So where does science come down on organics?There have been many studies over the years to find out just that. American Vegetable Grower® reached out to leading production researchers to share the studies they find most significant. Some of these studies date back multiple years, but have withstood the test of time.

The Most Effective Tool for Changing Your Soil Microbial Profile Is Cover Crops

In this six-year study (“Cover Cropping Frequency Is the Main Driver of Soil Microbial Changes During Six Years of Organic Vegetable Production”), USDA-ARS researchers Eric Brennan and Veronica Acosta-Martinez took a look at which elements of organic production made the most difference in soil microbe health in tillage-intensive, high-input organic vegetable systems.

The study looked at three different soil management approaches:

- Cover crops and compost every year

- Compost every year plus a cover crop every 4th year

- A cover crop every 4th year without compost.

The first approach was the best for soil health regardless of if the cover crop was legume-rye mix, mustard, and rye. The primary reason, the researchers concluded, was not compost, but the annual inputs of fresh carbon from the cover crops that improved the soil food web.

The researchers also felt the results called for developing methods with reduced tillage in high-value vegetable systems. This raises important sustainability questions about vegetable systems – whether organic or conventional – without frequent cover cropping.

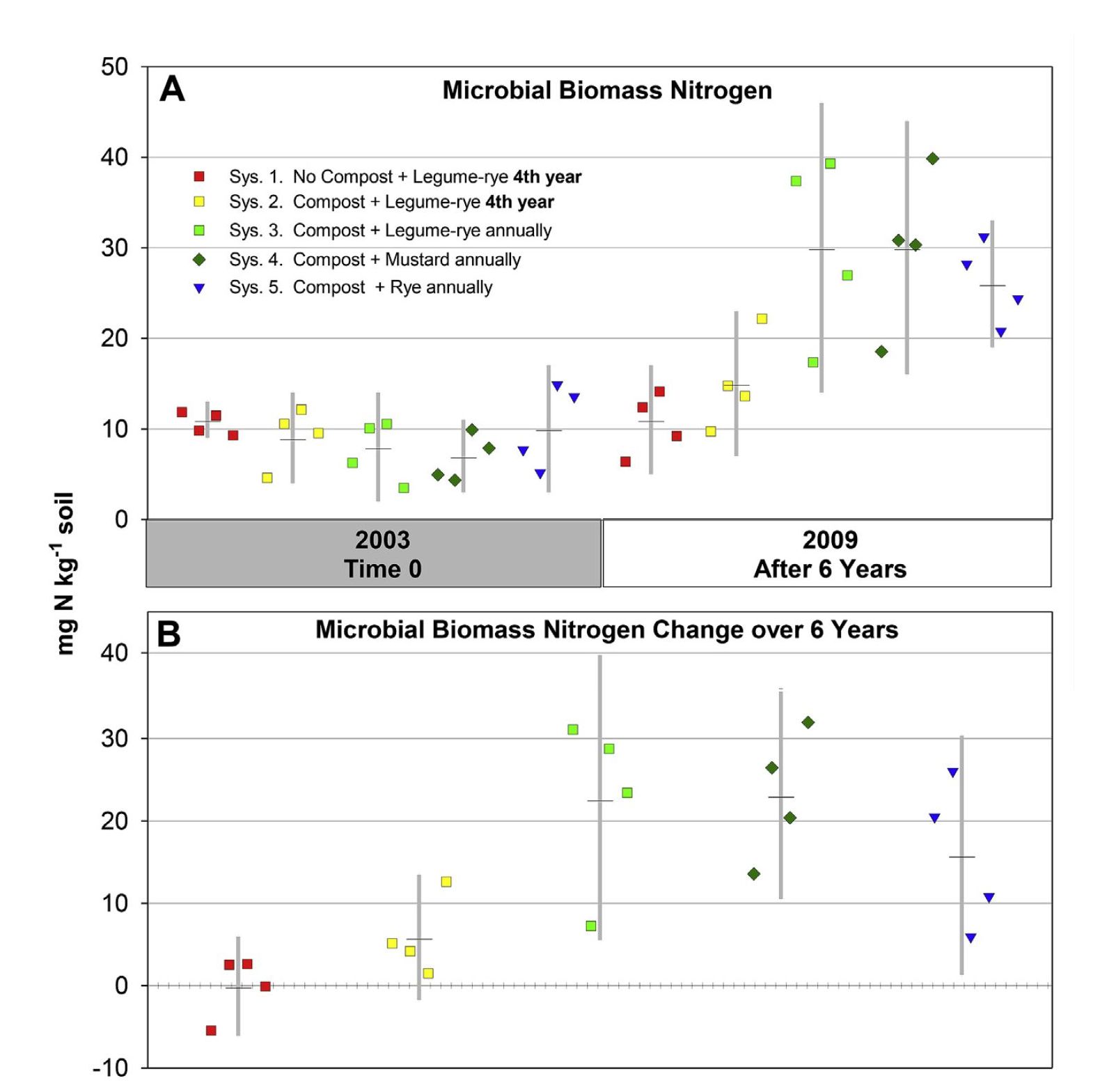

Here is a graphic that shows more detail of the study’s results:

Microbial biomass nitrogen at time 0 and after six years (A), and the difference (B) with five organic vegetable management systems that differed in annual compost additions (0 versus 15.2 Mg ha1 annually), and cover crop type (legume-rye, mustard, or rye), and cover cropping frequency (annually versus every fourth winter).

How the Soil Quality of Conventional, Organic, and Integrated Systems Compare

This seminal 1990s study (“Sustainability of Three Apple Production Systems”) led by Washington State University’s John Reganold compared Washington apple orchards and their production methods. Although conducted on apple crops, the results can likely be applied to vegetable crops. Among other results, the researchers found:

• Apple yields were similar for all three methods

• Soil quality was higher for both integrated and organic production systems

• Environmental impact was lower for both integrated and organic systems

• Organically produced apples had a higher profitability compared to the other two methods

The study concluded that both organic and integrated systems performed better than conventional ones, with organic edging out integrated in some areas.

How Cover Crops Affect Biomass, Microbial Diversity, and Nematode Communities

Ajay Nair (currently at Iowa State University) and Mathieu Ngouajio (USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture) tested both rye and rye-vetch as cover crops, with and without compost, on an organic tomato production system.

For this study (“Soil Microbial Biomass, Functional Microbial Diversity, and Nematode Community Structure as Affected by Cover Crops and Compost in an Organic Vegetable Production System”), the researchers analyzed soil from each plot at the end of the growing season over three years.

They looked at:

• Soil respiration

• Microbial biomass

• Metabolic quotient

• Nematode populations

The study was able to identify how different aspects of soil health are connected to one another:

Compost had a more pronounced effect on soil respiration. The highest was found in soils with both a rye cover crop and compost.

Microbial biomass had a direct correlation with attaining healthy levels of calcium, magnesium, and potassium.

Rye as a cover crop had the most impact on fostering a diverse soil, although rye-vetch performed well in this area.

Microbial communities responded more to compost than cover crops.

Nitrogen Management on Leafy Greens on the Central Coast

Specialists with different disciplines from the University of California (including American Vegetable Grower columnists Richard Smith, Vegetable Crops Farm Advisor; Michael Cahn, Irrigation Farm Advisor) set out to learn how nitrogen mineralization behaved in a number of situations. The group studied data collected throughout 2016 in the Central Coast area of California.

For this study (“Evaluation and Demonstration of Nitrogen Management of Organic Vegetable Production in Leafy Green Vegetables on the Central Coast”), the team ran 10 test plots on commercial fields for organic baby and romaine lettuce. The selection of sites ensured the soil types were diverse.

The group evaluated the effect of dry and liquid organic fertilizer and studied the nitrogen and phosphorus balance in organic production fields.

Top dressings of fertilizer were found to release less nitrogen into the soil than applications worked into the soil — 42% vs 70.2%. The first 10 days saw the strongest release of nitrogen from the fertilizer, after which the release amount slowed.

At first glance, the amount of nitrogen applied as a fertilizer was 1.2 to 4.8 times higher than the uptake by crops. But when the team assessed how much nitrogen was mineralized, the application amount was only 0.4 to 2.7 times what the crop used.

Nitrogen Type Makes a Difference in Nitrogen Soil Retention

The type of nitrogen impacts has a significant impact on long-term soil nitrogen retention, this 15-year study found (“Legume-based Cropping Systems Have Reduced Carbon and Nitrogen Losses”).

The research team, led by L.E. Drinkwater, who was with the Rodale Institute at the time and is now at Cornell University, conducted detailed micro-plot studies using a tracer to follow nitrogen. The study showed differences in how nitrogen is partitioned from organic vs. mineral sources, with more legume-derived nitrogen immobilized in microbial biomass and soil organic matter (SOM) than fertilizer-derived nitrogen.

The results show even in the study’s maize and soybean agro-ecosystems, plant-species composition and litter quality influence SOM turnover markedly.

“Greater retention of both carbon and nitrogen suggests that use of low carbon-to-nitrogen residues to maintain soil fertility combined with increased temporal diversity restores the biological linkage between carbon and nitrogen cycling in these systems and could lead to improved global carbon and nitrogen balances,” the researchers concluded.