El Niño Is Coming

El Niño is likely to be a factor for agriculture in the U.S. this year. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to say how much of a factor it will be.

In a June 26 webinar, “El Niño is Coming! Everything You Never Needed to Know About El Niño (and a few things you should),” Jeff Doran, Planalytics Sr. Business Meteorlogist says there’s a 70% likelihood that we will be shifting into El Niño, and in fact, may already be in the beginning phases. The question remains how long and how strong that El Niño pattern will be – and those factors have a significant impact on whether it will be a positive for agricultural markets.

What is El Niño?

El Niño is a sustained warming of sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific. La Niña occurs when those temperatures are in a cooler phase.

El Niño conditions exist when those average sea surface temperatures are at least 0.5°F warmer than normal temperatures for five consecutive three-month periods.

While growers and farmers in the drought-stricken West are looking to El Niño and its cooler air temperatures and increased precipitation as salvation after several hot dry years, it’s important to note that El Niño is not really a “black or white” event.

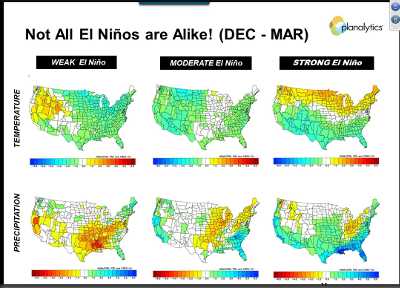

“Not all El Niños are alike,” Doran says. “The intensity of El Niño will be the major determinant in temperatures and precipitation amounts regionally in the U.S.”

El Niño events can be classified as weak (average sea surface temperatures > 0.5°F above normal), moderate (> 1°F above normal) or strong (>1.5°F above normal). The last El Niño period, from approximately August 2009 to May 2010, was classified as strong. We experienced La Nina conditions from 2010 to 2012, Doran says.

A strong El Niño weather pattern with its more moderate temperatures and increased precipitation would be beneficial for U.S. agriculture, particularly in the West. Image courtesy of Planalytics.

El Niño’s Effect On Agriculture

More moderate temperatures across the board can be expected with El Niño.

“That’s pretty decent news for agribusiness because we’ll see less extreme heat,” Doran says.

There are more significant differences in precipitation depending on the strength of an El Niño, however. With weak conditions, we shouldn’t expect to see precipitation much above normal levels. A moderate to strong classification, however, means much more chance for increased precipitation in the Midwest and West.

“A weak El Niño is not what we want,” Doran says. “That means cooler conditions than normal in the north. We won’t see more moisture in West, and some will shift to the Southeast.”

A moderate El Niño would be better for the corn belt with more moisture in the Midwest.

“We would like to be in a strong El Niño scenario,” Doran says. “That’s where the West will benefit.”

During the winter timeframe from December to March, we would likely see the most benefit with an increased snowpack which is critical for providing moisture to the West throughout the rest of the year.”

Some metrics aren’t pointing as strongly toward El Niño to this point. With an El Niño, easterly trade winds weaken, and that hasn’t happened yet. Two other measurements, the Southern Oscillation Index and the Indian Ocean Dipole, also aren’t indicating an El Niño, although those conditions can change quickly, he says.

Doran puts the probability that we officially see El Niño conditions this year at 70%. “We are seeing considerable sea surface warming over last the last three months,” Doran says. “We can’t tell where we’ll be right now. We’re cautiously optimistic, though.”