Grafting Offers a Surprising Boost to Plants

Images courtesy of Washington State University

Grafted vegetables have risen in popularity in recent years due to grafted plants’ improved ability to respond to stress, a proven increase in yield, and the decreased need for fumigation and other chemical controls.

As part of an ongoing project, Carol Miles, Extension Specialist in horticulture at Washington State University, has been investigating vegetable grafting as an alternative method for controlling Verticillium wilt since 2009.

“In areas where we have a high level of Verticillium, we are seeing increased yield with grafting, mainly because the non-grafted plants don’t yield well,” Miles says. “So we see an increase in fruit number at harvest.”

Miles is part of a national team of researchers focused on vegetable grafting funded by the USDA Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI).

In this interview, Miles shares her research results with American Vegetable Grower® magazine on grafting watermelon and eggplant, including improvements in yield, the grafting process, benefits for growers, and more.

Q: How are the grafted plants responding to soilborne diseases?

Miles: The grafted plants are holding up well to Verticillium, and it really depends on the level of disease in the field. At relatively low levels, we don’t get a big difference due to grafting; but as the levels start to go up, you see a much greater difference between grafted and non-grafted plants.

The important thing to understand is that with watermelon, we don’t really have resistance for Verticillium wilt. What we have is tolerance. We get a three-week delay in disease onset and usually that gives us time to harvest the plant. At the end of the season, we do a stem assay of plants in the field. We look in the stem and we’re seeing the disease there, but it’s not necessarily exhibited by wilting or chlorosis.

Eggplant is more susceptible to Verticillium wilt than watermelon. We have not found a really strong tolerant rootstock. So, even with grafting, we have not prevented the disease. We’re still looking, but we haven’t found it. And at this point, unfortunately, Verticillium wilt is not simple to manage for eggplant.

Q: How are you grafting plants?

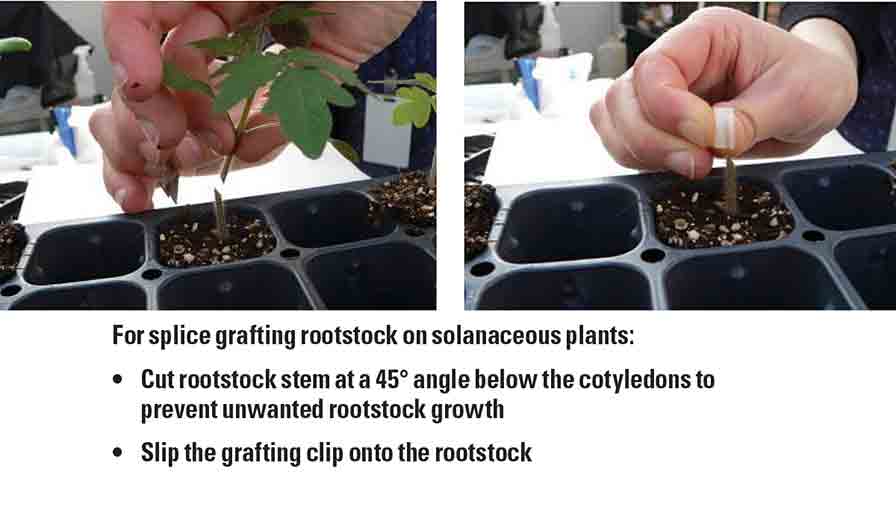

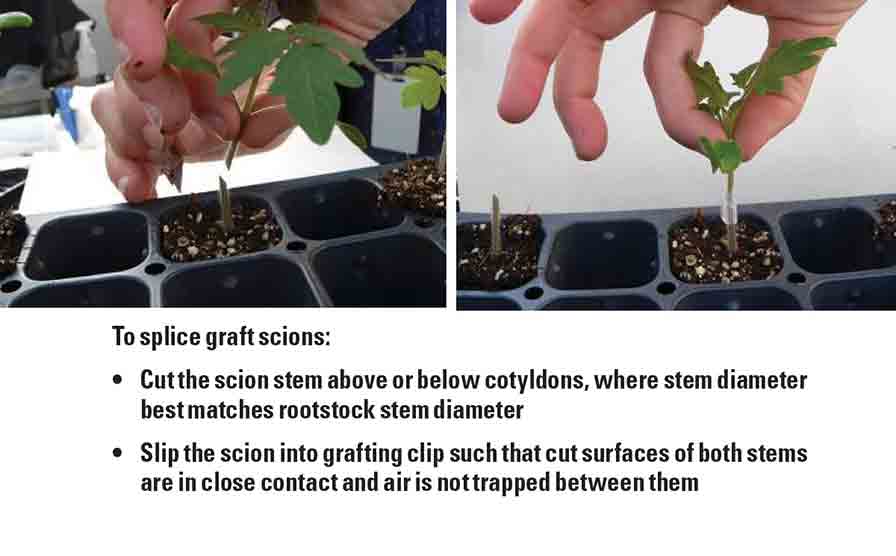

Miles: For eggplant, we use what’s called the splice graft.

Images courtesy of Washington State University

The splice is made below the cotyledons, and we do that at the seedling stage. It’s done at a 45° angle below the cotyledon so that both cotyledons are removed from the rootstock. That’s important because it removes the meristem tissue that’s in the leaf axil of the cotyledon, which would give you rootstock re-growth. You don’t want your rootstock to overgrow the variety you’re grafting on, so we remove both cotyledons from the rootstock.

And for watermelon, we use what’s called a one-cotyledon splice, which also is a splice graft, but it’s a little bit different because you leave one cotyledon on the rootstock. This is a 65° angle cut, so we leave one cotyledon on the rootstock, and then we scrape the base of the cotyledon with the edge of the cutting blade to take out the meristem tissue to prevent the regrowth.

Images courtesy of Washington State University

All of the grafting is done by hand, and we don’t do a lot of plants. We just do the plants for our research trials, which is maybe 500 or 600 plants per project.

Q: Is there any talk of automation for grafting plants?

Miles: A lot people are interested in automation. There are definitely grafting robots or grafting aids out there; however, they are still relatively expensive. It comes down to volume, and you have to be producing a relatively high number of plants to make it worth the investment. In our case, and for most small-scale growers who are grafting their own plants, it’s definitely not worth it.

Furthermore, a lot of these machines still require people to manage them, and the reality is that people can work pretty fast doing it by hand. In most cases, people can graft up to 300 eggplant or tomato plants per hour by hand and up to 250 watermelon plants per hour.

Q: What is the cost/benefit analysis to use grafted plants?

Miles: What we’re finding here in Washington is that you can use a grafted plant to control a disease, so you don’t necessarily have to use a fumigation application. If you look at using grafted plants instead of fumigation, then you can compare those costs. Also, for organic growers who don’t have access to fumigation, grafting provides them with an alternative disease management that they don’t have at all. Grafting is a very effective technique, and at a very low cost.

Q: What has been the grower reception with grafted plants?

Miles: There are a lot more grafted plants used in the U.S. today than there were even a couple of years ago; however, the U.S. has been slower to the game than our neighbors in Canada and Mexico.

What we need are really good demonstrations with various growers to show what a field of grafted plants looks like. Whereas in other areas in the world, they have maybe 10 acres, our growers have hundreds of acres. and we don’t have the capacity to make that number of grafted plants and demonstrate particular combinations.

However, this year, we’re going to start to see the beginning of more grafted plants and combinations as there are more grafters that can customize plants for growers.

Q: What are the research plans moving forward?

Miles: With watermelons, we’re interested in increasing the efficiency of grafting. We also want to increase the survival of grafted watermelon transplants in the grafting room.

One simple change we’ve made with watermelon is that we’ve gone from cutting at a 45° angle to a 65° angle. We feel the larger cut surface area gives a better take on grafting. We think this allows the vascular bundles to conjoin more quickly and completely between the rootstock and scion, providing water and nutrient transport between the top and bottom of the plant.

Alexander is a freelance writer and regular contributor to American Vegetable Grower® magazine.