NAFTA Renegotiation Long Overdue for Florida Farmers

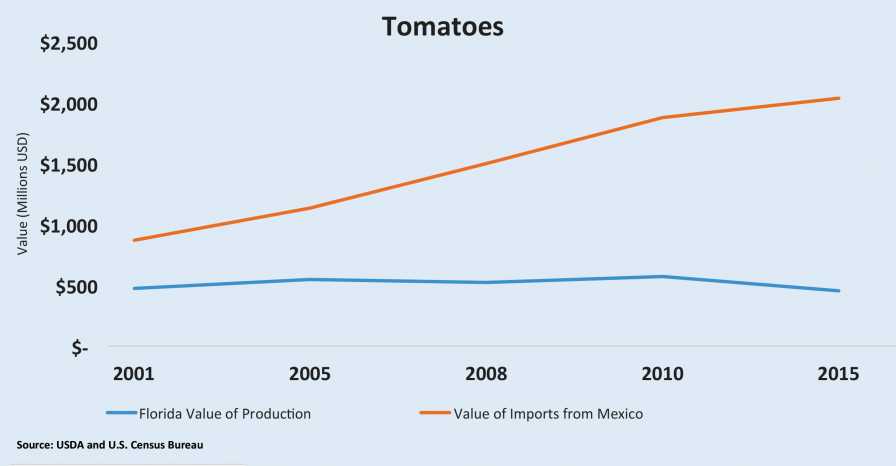

It’s easy to see the impact Mexican tomatoes have had on the Florida market in recent years.

Florida’s specialty crop growers are eagerly awaiting to see what form President Trump’s promised renegotiation of NAFTA takes. While other agricultural sectors have benefited from the trade pact that took force in 1994, it has been a negative for the state’s fruit and vegetable growers.

Tomato growers have taken a particularly hard hit from Mexican imports. In July, Reggie Brown, Executive Vice President of the Florida Tomato Exchange, took to Capital Hill to testify before the U.S. House of Representatives Agriculture Committee during a hearing on renegotiating NAFTA.

The picture Brown painted with the trade data is not a pretty one and illustrates the impact the trade deal has had on Florida growers and other growers in the U.S. A number of factors from pricing, subsidies, and much cheaper labor has given Mexico and unfair advantage, which is further enabled by NAFTA.

“We are not opposed to free trade,” Brown noted in testimony. “However, it must be fair trade. Unfortunately, the current trade environment under NAFTA has not fared as well for many U.S. fruit and vegetable producers, as we have heard concerns from many regions around the country including growers of Georgia blueberries and broccoli, Texas watermelon, California grapes and asparagus, and other specialty crop producers impacted under NAFTA throughout the nation.”

Downward Spiral

Brown noted that tomatoes are a vivid example of Mexico’s explosive growth in specialty crops. U.S. imports of tomatoes from Mexico increased from 1.2 billion pounds in 2000 to 3.2 billion pounds in 2016, a 166% increase. By comparison, U.S. tomato production fell from 2.7 billion pounds in 2000 to 1.7 billion pounds in 2016, nearly a 40% decrease.

“As Mexican volumes have soared and prices have fallen, U.S. fresh tomato growers have not been able to keep up with rising farm costs,” Brown noted. “Florida farmers have been forced to leave tomato fields unharvested. Numerous producers, especially smaller farms, have filed for bankruptcy. As confirmed by USDA figures, U.S. fresh tomato production is in serious decline, having lost almost 25% of total acreage since the inception of NAFTA.”

Mexico’s massive expansion of fruit and vegetable shipments to the U.S. is driving a agricultural trade deficit with the country higher. As of 2016, that deficient stood at $5.3 billion.

And, it’s not just tomatoes feeling the unfair competitive pressure. Since 2000, U.S. imports of Mexican strawberries have almost tripled. Imports of Mexican bell peppers have grown by 163%.

Feckless Enforcement

In 1996, U.S. tomato growers sought relief from the Department of Commerce (DOC) and International Trade Commission, submitting an antidumping petition on fresh tomatoes from Mexico. The result of the investigation was the DOC entered into a suspension agreement, which set a floor price for Mexican tomatoes being sold to the U.S.

Prior to sun setting, new agreements were entered over the years. In 2013, Mexican producers requested to the DOC to enter into a new suspension agreement. Despite two decades having passed since it collected dumping data in the 1996 investigation, the DOC did not collect new data on fair market values of Mexican tomatoes. The department then set reference prices based on the disastrous 2012 winter season and allowed Mexican importers to self-monitor their level of dumping. U.S. growers petitioned to terminate the agreement. They await a court’s decision on the matter.

Shady Subsidies

Compounding the unfair trading schemes, Mexico has established a subsidy system aimed at increasing yields in protected agriculture farms to achieve higher yields and year-round production. In 2009 and 2010, the government there spent $189.2 million on nearly 6,200 acres of protected agriculture.

This year, the Mexican government set forth at least nine programs and 43 components to support agriculture. These regulations specifically authorize greenhouse incentives of up to $48,000 per hectare. Other reports found subsidies for new greenhouse installations are as high as $162,000 per hectare.

In the case of tomatoes, these programs are not aimed at their consumers. Mexican growers do not grow tomatoes for Mexican consumers; they grow them to send to the U.S. market.

“These benefits, which are aimed at year-round production for Mexican fresh fruits and vegetables, have already put Florida producers at serious risk, and in time, will compromise all U.S. fruit and vegetable production if corrections are not made,” Brown noted.

“The Mexican industry’s considerable labor wage disparities only add to its unfair advantages,” Brown added. “The estimated annual Mexican wage advantage in the agricultural sector is $1 billion. Mexico’s farm laborers are paid about 10% of what U.S. farm laborers are paid for similar work.”

Brown concluded his testimony asking that Congress, along with the Trump Administration, work with Florida’s specialty crop growers to seek short-term remedies and longer-term efforts like the renegotiation of NAFTA to ensure the state’s growers can survive and thrive in the future.

What Are We Looking For?

Florida’s specialty crop sector was encouraged by the Trump Administration’s Summary of Objectives for the NAFTA Renegotiation, which laid out the following goals:

● To improve the U.S. trade balance and reduce the trade deficit with NAFTA countries;

● To seek a separate domestic industry provision for pesticide and seasonal products in antidumping/countervailing

duty proceedings;

● To preserve the ability of the U.S. to vigorously enforce its trade laws, including the antidumping, countervailing duty, and safeguard laws

● To require NAFTA countries to have laws governing acceptable conditions of work with respect to minimum wages, hours or work, and occupational safety and health.