What You Can Do About Organic Fraud

On its face, the domestic organic produce market has never been stronger. The most recent numbers from the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) paint a particularly robust picture: almost 25,000 certified U.S. organic operations sold a total of $8 billion in organic farm goods in 2016.

On its face, the domestic organic produce market has never been stronger. The most recent numbers from the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) paint a particularly robust picture: almost 25,000 certified U.S. organic operations sold a total of $8 billion in organic farm goods in 2016.

On the import side of the coin, we currently purchase just over $2 billion in organically certified agricultural products annually from allies and trade partners around the globe.

Below the surface, however, a looming threat to the USDA-Certified brand hangs like a cheap, ill-fitting suit: Organic fraud from imports. It threatens to squeeze out U.S. producers by weakening the higher prices that make organic production appealing to many growers.

Just how widespread is this issue? Nearly 60% to 70% of the agricultural products imported into the U.S. under the USDA-certified organic brand have the potential be fraudulent, or so claims The Organic Farmers’ Agency for Relationship Marketing (OFARM). This figure includes all ag products, not just produce.

So what can you do to help regulators protect your premiums and the organic market from this threat?

To know that, you must first understand how organic fraudsters are gaming the system.

The Most Common Forms of Fraud

“A lot of our imported, organic vegetables are coming from Mexico or Central and South America. And there’s actually a couple different avenues for fraud in that regard,” John Bobbe, OFARM’s now-retired former Executive Director, says from his office on his farm in Central Wisconsin.

One method of organic fudging is simply producing an “organic” crop with non-USDA certified inputs (i.e., conventional). Or even contaminated water or fertilizer. Or one might use conventionally grown seed in an organic production system.

Yet another avenue is importer funny business. In the simplest of terms, a load of agricultural produce — it could be blue maize from Argentina or crates of rainbow papaya from Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula — leaves port as conventional and then shows up at a U.S. port of entry and the accompanying paperwork has magically transformed to being labeled “USDA-Certified.”

Crazy how that happens, right?

We Need to Strengthen the Weak Link

According to Bobbe, the common thread throughout this entire narrative is the very USDA agency tasked with enforcing the standards of the organic program: the NOP.

“It all goes back to the National Organic Program in the first place, which today is the weak link in the whole entire organic food chain,” Bobbe states. “As far as I am concerned, they are the weakest link in the entire world.”

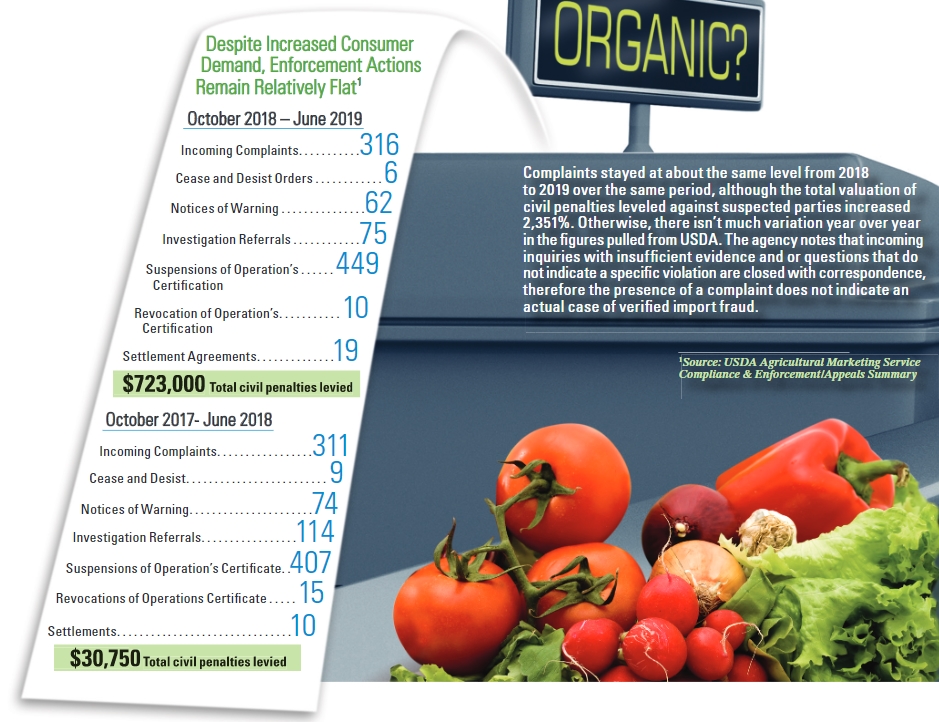

At the heart of Bobbe’s issue with NOP’s enforcement efforts is that the mechanism for enforcement – monetary fines – is basically toothless. Think about it. Importers stand to profit sometimes in the millions from a load of organic produce. And the current maximum fine NOP can levy is a paltry $5,000. That’s a spit in the bucket for some of these criminal enterprises.

“This is small potatoes,” Bobbe says.

Increased Demand Stresses Ports

“Our biggest challenge (in organics) is that the demand continues to way out pace the supply, thus incentivizing the very import fraud we’re discussing here,” notes Michael Sligh, who helped draft the original standards that helped shape the USDA-certified organic program.

Sligh is a founding father of the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) and an organic farmer himself.

That robust consumer demand, he says, is a good problem to have. But it’s also why the U.S. is stuck importing as much produce as we do. And that, in turn, puts increased pressure on NOP and its inspectors at our borders and ports to ensure imports meet the same standards domestically produced products are held to.

“This requires greater coordination between USDA, Port Authorities, Food Safety, Foreign Ag Services, and an array of federal agencies and other governments,” he says.

And it’s not just the number of agencies and organizations that complicates matters. Each also needs strong agreements, Memorandums of Understandings (MOU), training, and sophisticated instructions to work effectively, he states.

Fraudsters Take Advantage of the Stressed System

Sligh proposes shifting to a more risk-based fraud prediction model, one that incorporates overseas production data with intra-agency intelligence sharing. He is echoed by Harriet Behar, the current chair of the NOSB, in that regard.

“Right now, we’re still so busy trying to get caught up on what’s happening. We need to start thinking in terms of 21st century technology and tracking,” she says.

Today’s method uses an old technology: importers fax a certificate.

“It is important to remember that these are not just American problems and challenges. They are global ones,” Sligh adds.

Still, anytime we’re importing billions of dollars of tomatoes and other perishable produce, there are going to be challenges. And temptation. The higher prices organic produce earns over conventional is a big incentive for shady characters to get involved.

The end goal, all sources contacted for this story agree, is to have very clear, uniform product traceability and labeling requirements from farm to final retail buyer. And that data must be accessible and clearly communicated, as well as understood by inspection teams, at every step of the import process.

A Paper System in a Digital Universe

Before the advent of digital technologies and wide-scale network connectivity, the organic certification program “kind of grew up on paper” says Behar, who is also a small plot organic herb and vegetable farmer.

“When most trade was from one state to another, you could call somebody up and check and it was a lot easier, you know? Now, with all of this international trade it is very difficult,” she says.

First, there’s the language barrier. Certificates from the point of origin generally are in that country’s native language.

Another challenge is some produce comes from well-established systems that differ from the U.S. Take the E.U. It has different processes and ways of communicating. And well-developed systems like the E.U. tend to be fast-tracked.

“We have equivalency with them. So, we are saying that if it is European certified organic, then we accept that,” Behar says.

She sees many of the coming digital technologies helping NOP and agents at the border get out ahead of fraud before it reaches our borders and ports.

“We’re trying to move toward having some Blockchain technology or electronic certificates,” she says.

It would be much simpler to have a system where the certified entity contacts the certifier, and then the certifier contacts the buyer and verifies that what is being sold is indeed organic, Behar says.

Educating Inspectors and Some Help from Congress

Today, Behar and those at the NOSB are waging battle against fraudulent organic imports on two fronts: by educating U.S. Customs and Border Patrol [CBP] law enforcement officials on the frontlines, and by using the resources and additional funding for standards enforcement provided in the 2018 Farm Bill.

“We’re just starting to work with CBP to have them understand that when something is labeled as organic and it is coming into the U.S. that it can’t be fumigated. Or if it is fumigated, then the name on that load needs to change to say non-organic,” Behar explains.

The 2018 Farm Bill expands resources and authority for organic import enforcement. That’s mainly via an extra $5 million in funding for USDA data collection efforts around curbing fraud.

“There was some really good language [in the Farm Bill],” Behar concedes.

Still, legislative fix-alls being the rare bird they are, Behar would like to see regulators hold organic import traceability data to the same standards as domestic U.S. producers’ data.

Currently she sees clear inconsistencies in the level that domestically grown produce is scrutinized as compared to imported produce. Where domestically you have a robust digital paper trail for inspectors to examine, imports are mostly rubber-stamped based on the verification of easily forgetable certificates.

“I feel pretty good about what happens here in the U.S. But again, I don’t know what is happening overseas,” Behar says.

National Organic Program Responds

We reached out to officials with USDA NOP for comment on many of the claims and assertions made throughout this article.

“Increased federal intra-agency coordination and cooperation among all enforcement agencies is key to protecting that seal, as well,” NOP said in its response.

If you’d like to read NOP’s full response, we’ve published it on our website, GrowingProduce.com/tag/NOP.

Consumers May Lose Confidence in Organic Produce

The ones hurt the most by organic import fraud are America’s end consumers.

For instance, in the case of a 2016 fraudulent imported pineapples case from Costa Rica, it was American citizens — not the food processors or manufacturers, not the fraudulent importers — that were duped out of $6 million by purchasing fraudulent organic produce.

“I want them to have trust in our label, and know that I am going to be giving them what they’re expecting, using the tools that nature provides to improve soil fertility, crop health, protect against pests and diseases, support pollinators, and improve the natural resources of my farm,” Harriet Behar, the current chair of National Organics Standards Board, says. “All of those are things that they are expecting as organic consumers, and as a certified organic producer I am doing them. When something fraudulent comes along and breaks that trust, it’s hard to overcome that.”

What’s a Farmer to Do?

Any organic producer reading this story is likely asking themselves the same question at this point: Ok, but what now? What can I do to make a difference?

Sligh harkens back to an age-old adage.

“The old saying ‘the squeaky wheel gets the grease’ remains my best advice,” he says. “Talk to your members of Congress and urge this along.”

Here are some talking points you may want to raise:

Apply pressure for NOP to implement new regulations. There has been recent movement to report, with the U.S. House Ag Subcommittee recently hosting an USDA/NOP oversight hearing. Many of the issues were raised with very strong support. Lawmakers repeatedly urged NOP to implement the new regulations from 2018 Farm Bill passage as soon as possible.

Give NOP more money to implement inspections. Additionally, growers that secure an audience with their congressional rep should request stepped-up funding for NOP and its inspection programs, as well as great coordination between agencies at the border.

Increase fines for violators. A $5,000 fine for those companies caught committing organic labeling fraud is a minor cost of business for them. It does little to protect American organic growers who comply with regulations.

For Behar and her cohorts at NOSB, it goes back to striking while the iron is hot. Or, perhaps, when the (organic) hay is

in the barn.

Right now, growers in the U.S. have “an incredible opportunity” to meet the organics market demand, she notes. But being an organic producer is also rewarding. You see your land improve and you’re able to pass on an improved ecosystem to the next generation.

“It’s very rewarding to work within nature.”